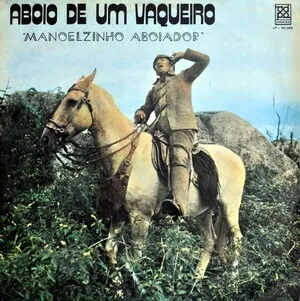

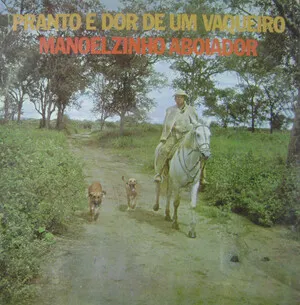

Aboio cantado is the sung form of aboio, a traditional cattle-herding call from the Brazilian Sertão, especially the Northeast. It is performed by vaqueiros (cowboys) to guide, calm, or gather cattle across open rangelands.

Musically, it is typically a solo, unaccompanied chant with free rhythm, long sustained vowels (often the emblematic “ê boi”), sliding intonation, and melismatic lines that carry far over distances. The timbre tends toward a bright, nasal projection to travel across the landscape. Texts may be improvised, evoking the herd, the horse, the drought and the caatinga, faith and saints, and the daily life of the vaqueiro.

As a work-song tradition, aboio cantado predates modern Brazilian popular styles and remains an emblem of the Sertão’s soundscape, while also permeating and inspiring later genres such as baião, forró, xote, and sertanejo raiz.

Aboio cantado arose with cattle ranching in the Brazilian Sertão during the colonial expansion of the 17th–18th centuries. Vaqueiros needed strong, far‑carrying vocal signals to move and soothe cattle across vast, semi‑arid ranges. The practice drew on Iberian herding calls brought by Portuguese settlers, interacted with Indigenous sound practices tied to landscape communication, and incorporated Afro‑Brazilian vocal aesthetics—yielding a distinct Northeastern cattle call.

Originally entirely functional, the sung aboio was performed at dawn, dusk, and during drives, using free rhythm, sustained vowels, and glissandi to project over distance. Over time, the call developed poetic verses: improvised lines praising the herd, narrating work, invoking saints for protection, and expressing the Sertão’s hardships and beauty. While largely solo and unaccompanied, local practice sometimes frames aboios within gatherings, processions, or religious observances.

Folklorists and collectors began documenting aboios in the early–mid 20th century, and recordings disseminated the sound beyond the ranch. Popular artists from the Northeast—most famously Luiz Gonzaga—wove aboio motifs and the feeling of the call into baião and other forró-related forms. Composer‑singers like Elomar and Xangai later recontextualized aboio within authored works, preserving its timbre and imagery while giving it concert and recording life.

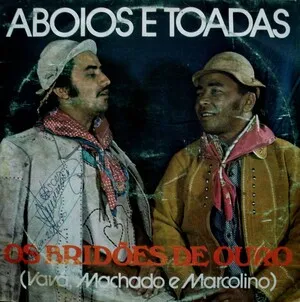

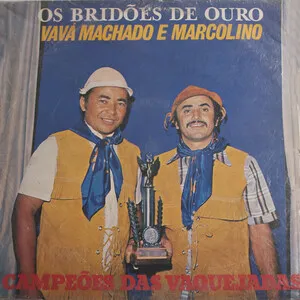

Today, aboio cantado survives both as living rural practice and as heritage showcased at vaquejada festivals, community events, and religious ceremonies such as the "Missa do Vaqueiro" in Pernambuco. Cultural organizations, local archives, and artists continue to record and teach the tradition, underscoring its role as a sonic emblem of Northeastern identity and pastoral memory.