Yukar is the epic narrative chant of the Ainu people, traditionally performed solo in a steady, speech‑song delivery without instrumental accompaniment.

It tells long mythic or heroic tales—often in the first person as a speaking deity (kamuy)—using dense formulaic diction, parallelism, and refrains to aid memory and create a trance‑like flow.

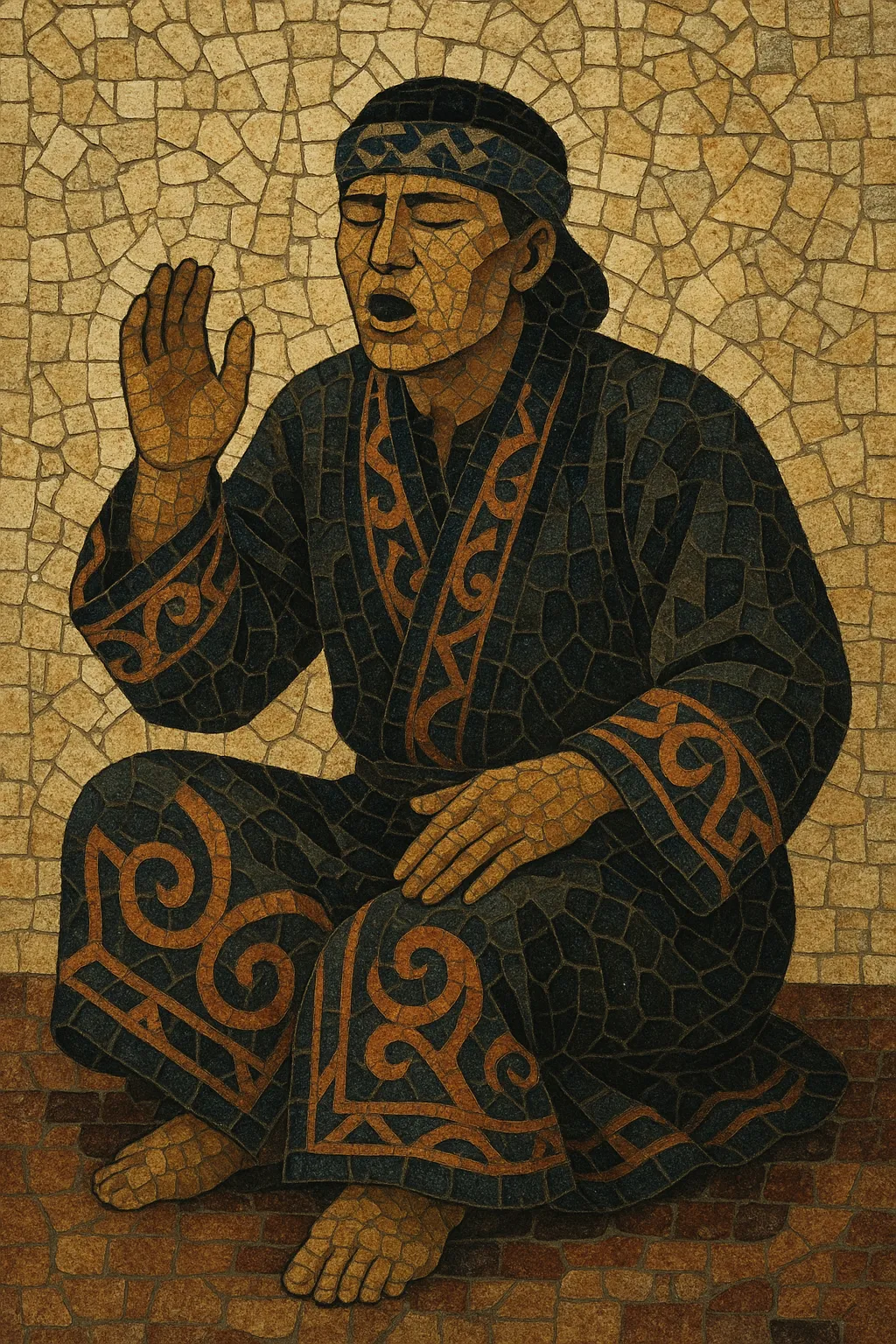

The vocal line is narrow in range, rhythmically pulsed by breath, hand‑tapping, or knee‑tapping, and shaped by vocables and ideophones that punctuate the story.

Distinct from Ainu group songs (upopo), yukar functions as a dramatic, extended oral literature where performance and narration are inseparable.

Yukar arises from the oral epic tradition of the Ainu communities of Hokkaidō (Japan) and Sakhalin, likely many centuries before written documentation. It served as a vessel for myth, history, and cosmology—especially tales narrated by gods (kamuy yukar) and human heroes—transmitted by skilled reciters in domestic and communal settings.

From the 17th century onward, Japanese observers noted Ainu oral arts, but systematic collection surged in the late 19th–early 20th centuries. Key figures such as Imekanu (a renowned teller) and Yukie Chiri (who transcribed and translated yukar into Japanese in the 1920s) preserved major cycles. Linguists and folklorists (e.g., Kindaichi Kyōsuke) recorded extensive texts, stabilizing versions that might otherwise have been lost amid assimilation pressures.

20th‑century urbanization and language loss reduced everyday performance, yet archival recordings and publications sustained scholarly and community interest. From the late 20th century onward, Ainu cultural revitalization—led by elders and cultural advocates like Shigeru Kayano—sparked renewed teaching and public recitation. Contemporary Ainu artists sometimes weave yukar texts or performance aesthetics into concerts, education, and intercultural collaborations, keeping the narrative chant alive while respecting its traditional solo, unaccompanied core.