Valencian folk music refers to the traditional vocal and dance music of the Valencian Country (eastern Spain), encompassing street-processional repertoires for dolçaina (shawm) and tabal (tabor), village rondalla string ensembles, and ornate solo song forms such as cant d'estil and albaes.

It features lively dance genres (jota, dansà, fandango variants), solemn processional pieces linked to guilds, human-tower rites (muixeranga), and festive cycles (Falles, street dances). Melodically it is often modal (Dorian, Mixolydian, Phrygian inflections), rhythmically driven by duple-step dances and brisk triple-time jotas, and textually rooted in the Valencian language, with themes ranging from love and satire to historical memory.

While its roots are medieval and early modern, the repertoire was systematized and brought to recordings during the 1970s folk revival, which fused archival research and field collecting with contemporary arrangements.

Valencian folk music traces back to medieval and early modern community music-making: processional shawms and drums for civic and religious rites, rondalla string ensembles for social dances, and a rich vernacular song tradition in Valencian. Dance-song families such as the jota, seguidilla, fandango, and locally named danses were adapted to local steps and texts. The dolçaina (locally also xirimita) with tabal became emblematic of street soundscapes.

Urban wind bands flourished across the region, and local dance-song forms were maintained in village festivities, while solo vocal styles like cant d'estil and nocturnal albaes developed strikingly melismatic delivery and improvised verses. Despite modernization, oral transmission persisted through festivities (Falles, Moors and Christians, romerías), guilds, and family ensembles.

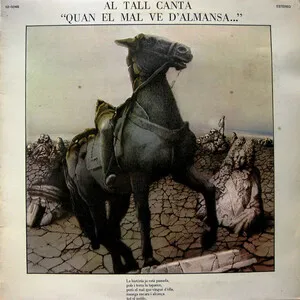

From the mid-1970s, artists and researchers led a revival that documented field repertoires and re-contextualized them on stage and record. Groups such as Al Tall gathered variants of jotes, fandangos, danses, and work songs, arranging them with rondalla instrumentation and modern harmonies while keeping modal and rhythmic identities intact. This period anchored Valencian folk within the broader Iberian folk renaissance and the singer-songwriter milieu.

A second wave professionalized performance practice (dolçaina pedagogy, archival editions) and broadened aesthetics: ensembles like Urbàlia Rurana and artists such as Miquel Gil and Pep Gimeno “Botifarra” combined fieldwork authenticity with contemporary production. Crossovers emerged with Mediterranean folk, early music, and folk-rock. Today, Valencian folk thrives in festivals, dance gatherings, and education, with the Valencian language and local ritual calendars continuing to frame its living tradition.