Trás-os-Montes folk music is the traditional music of Portugal’s far north‑east, especially the Terra de Miranda plateau along the Spanish border. It is best known for the gaita-de-foles transmontana (Transmontan/Mirandese bagpipe), the three‑hole pipe and tabor pairing (flauta e tamboril), frame and tambourine percussion, and vocal practices rooted in village ritual life.

The repertoire ranges from lively stick‑dances of the Pauliteiros de Miranda to processional tunes, work songs, winter carols, and strophic narrative ballads. Melodies often ride over a sustained drone, use modal pitch collections (frequently Mixolydian and Dorian), and feature tight rhythmic drive in duple or compound meters suitable for circle and line dances.

Culturally, the style carries the identity of the Mirandese-speaking minority and reflects centuries of cross‑border contact with nearby Leonese and Galician traditions. Modern ensembles balance historically informed performance with contemporary stage presentation, keeping local dance, costume, and instruments at the center.

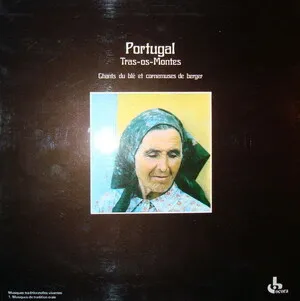

Trás-os-Montes folk music grows from rural life in Portugal’s north‑eastern highlands, with especially strong roots in Terra de Miranda (around Miranda do Douro). Oral transmission anchored the songs and dances, which accompanied agricultural cycles, religious festivities (Christmas “cantares ao Menino,” Epiphany rounds, and processions), and community gatherings.

By the 18th–19th centuries, a recognizable instrumental core was established: the gaita-de-foles transmontana (regional bagpipe) with bombo (bass drum) and caixa (side drum), the three‑hole flauta accompanied by a single tabor (tamboril) played by the same musician, and an array of pandeiretas and pandeiros (frame/tambourine percussion). Hurdy‑gurdy (sanfona/zanfona) and wire‑strung violas (e.g., viola mirandesa) appear in some locales. Dances like the Pauliteiros stick dances developed distinctive step vocabularies and figures, while songs favored strophic forms with call‑and‑response and syllabic delivery.

Proximity to Zamora and León in Spain fostered exchange with Leonese and Sanabrian traditions; the mix of pipes, drums, and modal tunes echoes broader Iberian and Atlantic‐Celtic sound worlds. The Mirandese language (an Astur‑Leonese variety) colors the sung repertoire and toponyms, marking the music as a cultural emblem for the region.

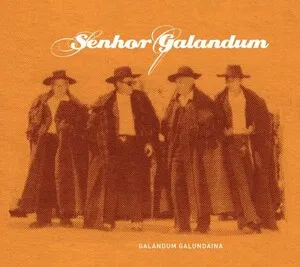

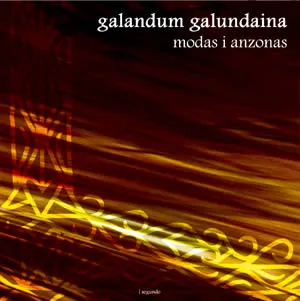

Twentieth‑century folklorists, local cultural associations, and municipal archives documented tunes and dances as rural lifeways changed. From the late 20th century onward, professional and semi‑professional groups brought village repertories to national and international stages, coinciding with the growth of Iberian and pan‑Celtic festivals (notably the Festival Intercéltico de Sendim), which connected Trás‑os‑Montes with Galician, Asturian, and broader European folk circuits.

Contemporary performers combine historically informed techniques (ornamentation, drones, dance tempos) with modern arranging and recording. Youth teaching, local festivals, and cross‑border collaborations sustain transmission, while staged performances keep the Pauliteiros dances, Mirandese bagpipe, and seasonal song traditions in the public eye.