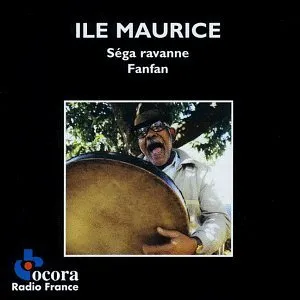

Traditional séga is a creole dance-music of the Mascarene Islands, especially Mauritius, born among enslaved African and Malagasy communities and later embraced across society. It is performed with hand percussion (ravanne frame drum), the maracas-like kayamb/maravanne shaker made from cane, and a metal triangle, sometimes joined by the bobre (musical bow) and voice.

Its defining feel is a lilting 6/8 or 12/8 swing with a swaying, circular pulse that invites communal dancing. Vocals are typically in Mauritian Creole (and related French-based creoles), using call-and-response and expressive melisma. Lyrics range from playful and flirtatious to topical and satirical, reflecting everyday joys and hardships.

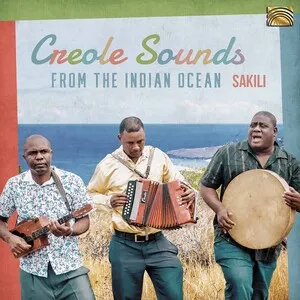

Unlike modern, electrified séga, the traditional form is acoustic, earthy, and rhythm-driven. It is both a music of celebration and a vessel of memory, carrying traces of African, Malagasy, and European (e.g., colonial-era dance) influences while remaining unmistakably island Creole in identity.

Traditional séga emerged in the Mascarene Islands under French and later British colonial rule, principally in Mauritius, among enslaved Africans and Malagasy people. In clandestine night gatherings, people sang in creole, beat the ravanne, shook the kayamb/maravanne, and marked time with a triangle. The music’s core pulse and call-and-response vocals reflect African and Malagasy practices, while certain dance gestures and formal song shapes show the imprint of European social dances that were heard in colonial settings.

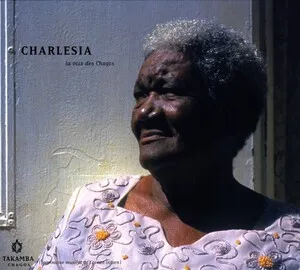

After emancipation, séga continued as a community practice tied to festivities, courtship, and social commentary. Early written descriptions highlight its circular dance, the percussive trance-like groove, and the emotive, sometimes improvised singing. By the mid-20th century, performers began to be recorded and broadcast locally, and the genre’s repertoire grew into a body of beloved creole songs.

From the 1960s, traditional séga entered theatres, radio, and records, shaping a shared island identity. As tourism and urbanization rose, an electrified, band-oriented “séga moderne” developed, adding guitars and keyboards. Meanwhile, the acoustic, percussion-led “séga tipik/traditional séga” remained the touchstone for authenticity. In the late 1980s, new fusions emerged (most famously seggae, blending séga and reggae), but they continued to draw on the traditional rhythmic bedrock and creole poetics.

Traditional séga is celebrated as an emblem of Mauritian and wider Mascarene Creole heritage. Community ensembles, dance troupes, and cultural advocates teach the ravanne, kayamb, and classic songs to younger generations. International recognition (including UNESCO inscription for séga tipik of Mauritius) has supported safeguarding efforts, workshops, and festivals, helping the tradition thrive alongside its modern descendants.