Tigrinya music is the traditional and contemporary music of the Tigrinya-speaking people of Eritrea (and the adjoining Tigray region). It blends deep highland folk roots—krar (lyre), kebero (double-headed drum), handclaps, and ululations—with later urban instrumentation such as electric krar, guitar, accordion, and keyboards.

Melodically, it draws on the Horn of Africa’s pentatonic qenet system (notably Tizita, Bati, Ambassel, and Anchihoye), with highly ornamental vocals, call-and-response refrains, and proverb-rich Tigrinya lyricism. Dance-driven styles like guayla emphasize propulsive, syncopated grooves in 2/4 or 4/4, while more reflective songs carry a nostalgic, longing character. Since the cassette era, modern production has incorporated drum machines, synths, and diasporic influences without losing its signature vocal and rhythmic identity.

Tigrinya music is rooted in the highland cultures of present-day Eritrea (and neighboring Tigray), where communal singing, circle dances, ululation, and instruments like the krar (six-string bowl lyre) and kebero have been central for centuries. Liturgical chant traditions from the Eritrean/Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church shaped melodic aesthetics, while folk song forms preserved local histories, pastoral life, and social customs.

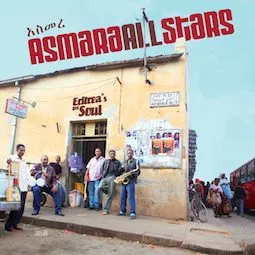

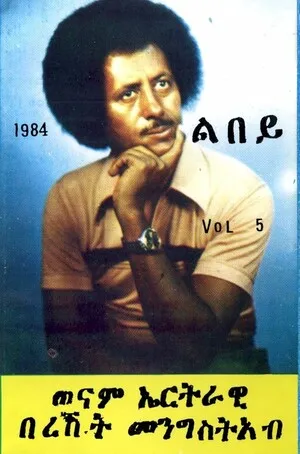

With colonial and postcolonial urban life in Asmara and other towns, ensembles began adopting accordion, guitar, and brass, and studios and radio stations supported recording. By the 1960s–70s, a recognizable modern Tigrinya sound took shape on radio and cassettes: dance styles like guayla flourished, and singer-instrumentalists popularized the electrified krar. Songs often carried coded social commentary and, during the Eritrean struggle, themes of resilience and identity.

Cassettes enabled rapid circulation across the Horn of Africa and the global diaspora (Sudan, the Gulf, Europe, North America). Producers folded in keyboards and drum machines, but retained the core pentatonic melodies, call-and-response choruses, and percussive clapping patterns. After Eritrea’s independence (1993), music videos and national media amplified the scene, while cross-border exchange with Tigray continued to shape repertoire and style.

In the 2000s–2010s, artists combined traditional timbres with contemporary pop, reggae, and R&B touches, while preserving the characteristic vocal ornamentation and dance-ready rhythms. Digital platforms broadened international audiences, and live shows in the diaspora sustained an active performance circuit. Despite modernization, the genre’s identity remains anchored in Tigrinya language, pentatonic modal practice, and the communal energy of guayla dance.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)