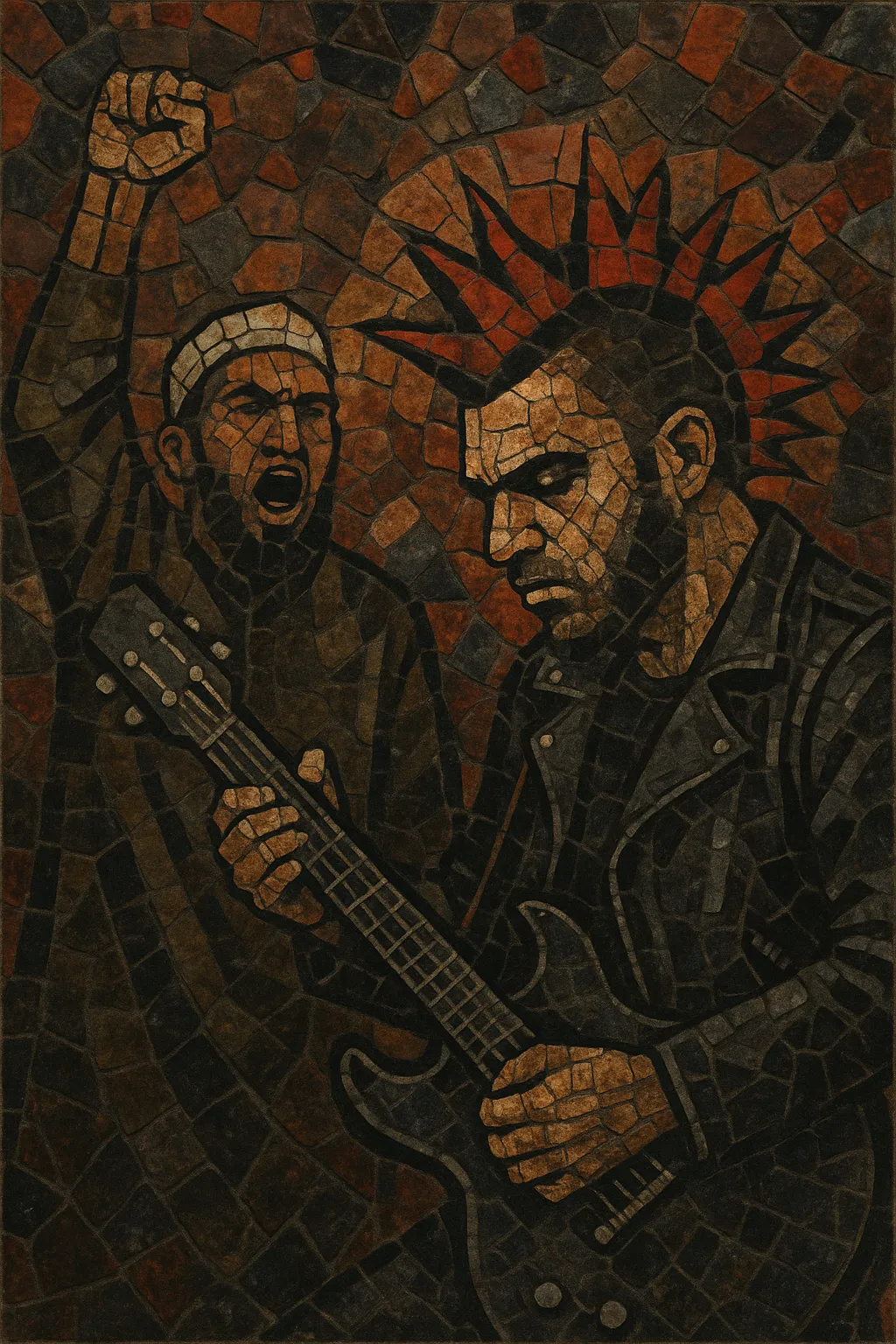

Taqwacore is a Muslim-centered punk movement that fuses the speed, rawness, and DIY ethic of punk rock with lyrical themes about faith, identity, diaspora, and political dissent. It emerged in the mid‑2000s after the publication of Michael Muhammad Knight’s novel The Taqwacores, which imagined a house full of Muslim punk misfits and helped catalyze a real-world scene.

Musically, taqwacore leans on punk rock and hardcore templates—fast tempos, power‑chord riffs, shouted/sung vocals—while sometimes drawing on South Asian or Middle Eastern rhythmic accents, language mixing (English with Urdu, Punjabi, Arabic, etc.), and occasional melodic turns suggestive of Hijaz/Phrygian-dominant modes. Lyrically, it is openly confrontational and self-reflective, critiquing Islamophobia, racism, state surveillance, community gatekeeping, and rigid religiosity, while also celebrating complex Muslim identities.

Michael Muhammad Knight’s 2003 novel "The Taqwacores" envisioned a Muslim punk house and inadvertently provided a blueprint for a nascent scene. As the book circulated through zines, forums, and MySpace, young Muslim and Muslim‑adjacent punks in North America began organizing shows and forming bands that embraced a DIY ethos and a politics of visibility.

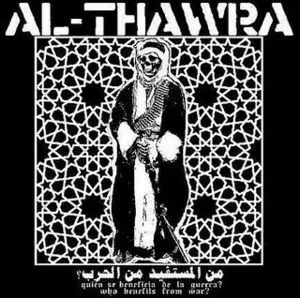

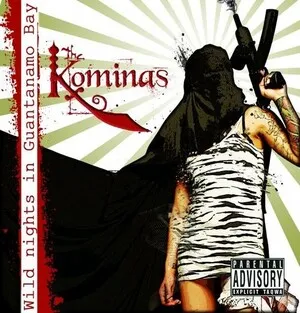

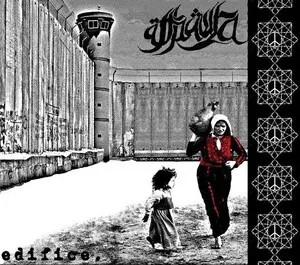

By the mid‑to‑late 2000s, groups like The Kominas (Massachusetts), Al‑Thawra (Chicago), and Secret Trial Five (Vancouver) embodied the sound and stance: fast, abrasive punk framed by lyrics taking on Islamophobia, surveillance, gender politics, and diasporic tensions. Documentaries and films amplified the moment—most notably Omar Majeed’s documentary "Taqwacore: The Birth of Punk Islam" (2009) and Eyad Zahra’s feature film adaptation "The Taqwacores" (2010)—alongside DIY tours and college‑town circuits.

As coverage spread, artists and collectives appeared in the U.S., Canada, Pakistan, and beyond, some adopting the taqwacore label and others resisting it as a media tag. Internally, the scene debated representation, identity politics, and what counted as "Muslim punk," while musically it remained rooted in punk/hardcore with occasional nods to South Asian rhythms or modal gestures.

While never a mass commercial genre, taqwacore carved out cultural space for Muslim‑identified and allied punks, broadened conversations around religion and subculture, and influenced subsequent South Asian and Muslim‑diaspora punk/DIY activity. Its legacy endures less as a fixed sound and more as a toolkit—DIY organizing, fearlessly political lyrics, and unapologetically complex identity work.