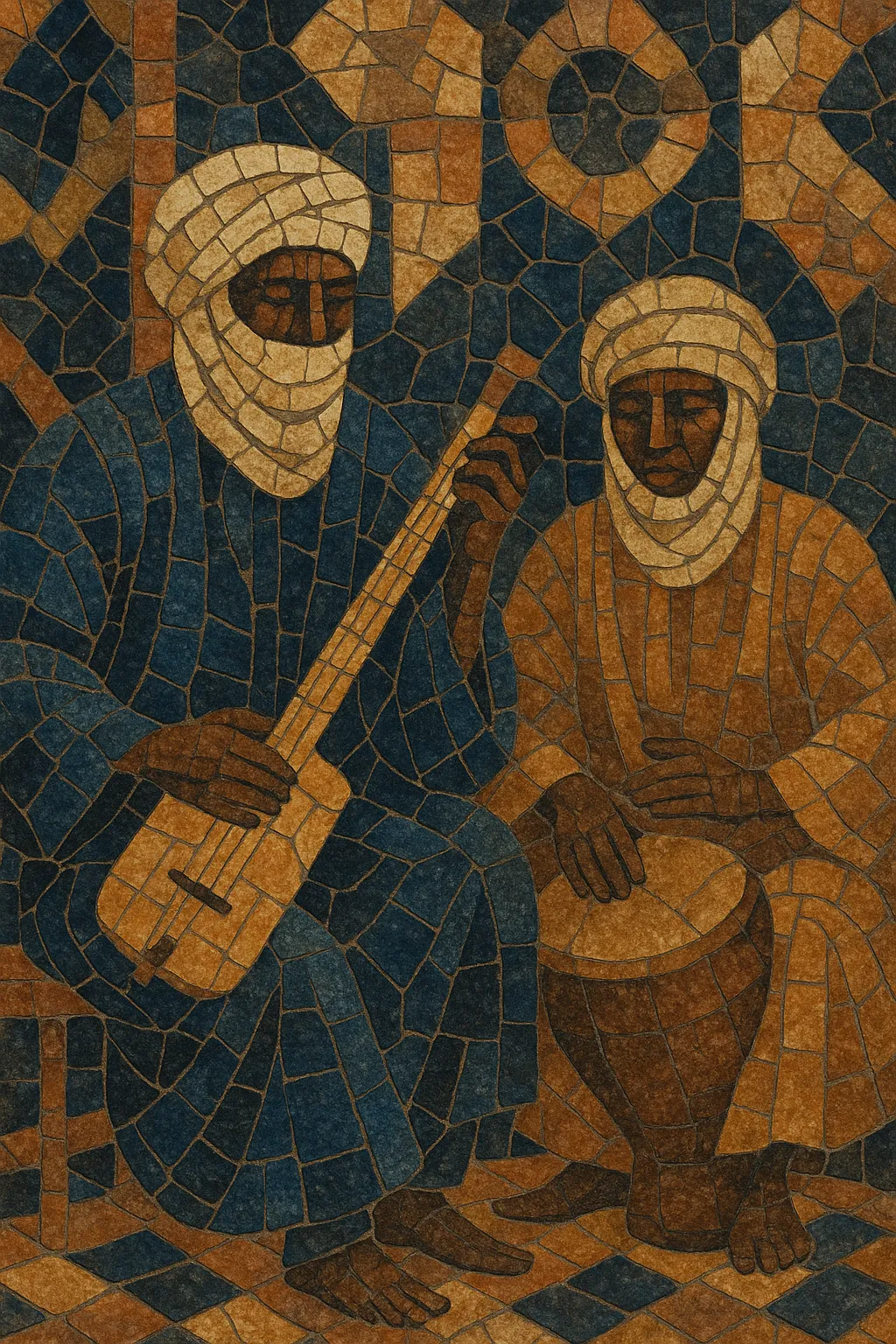

Takamba is a traditional Songhai–Tuareg music and dance style from northern Mali (and adjacent Niger), performed on a loping 6/8 groove that invites steady, trance-like movement. The core ensemble features a plucked skin-lute (known variously as the tehardent/kurbu/ngoni) and an inverted calabash struck by hand, supporting call-and-response vocals and praise singing.

Marked by cyclical ostinatos, subtle polyrhythms, and hypnotic repetition, takamba accompanies community celebrations, weddings, and patron-honoring ceremonies. Dancers often begin seated, undulating shoulders and arms in restrained, graceful gestures before rising, embodying the music’s cool yet propulsive swing.

Takamba emerged among Songhai communities around the Niger Bend (Gao–Timbuktu region) in the 19th century, with strong interplay between Songhai and neighboring Tuareg musical practices. Historically tied to praise-singing lineages (griots) and local nobility, the music celebrated patrons, warriors, and communal milestones. Its name is associated with both the music and its characteristic dance, which begins in a seated posture and gradually rises in intensity.

The foundational pairing of the plucked skin-lute (tehardent/kurbu/ngoni) and inverted calabash creates a lean yet resonant texture. Melodic lines are modal and pentatonic-leaning, articulated in repeating motifs that encourage a trance-like state. Vocals—often antiphonal—deliver panegyric texts, moral aphorisms, and local histories, while handclaps and ululations heighten the communal atmosphere.

Through the colonial and postcolonial periods, takamba consolidated as a signature Songhai style at weddings, naming ceremonies, and regional festivals. Regional orchestras and radio dissemination broadened awareness, while the core village ensembles kept the intimate, cyclical performance format.

Since the late 20th and early 21st centuries, takamba’s rhythmic language has informed Tuareg guitar music and Sahelian “desert blues.” Some artists electrified the lute parts on guitar or synthesizer, while others retained the acoustic tehardent-and-calabash format. Labels and field recordings helped expose takamba internationally, yet the style remains rooted in community ceremonies and patronage traditions.