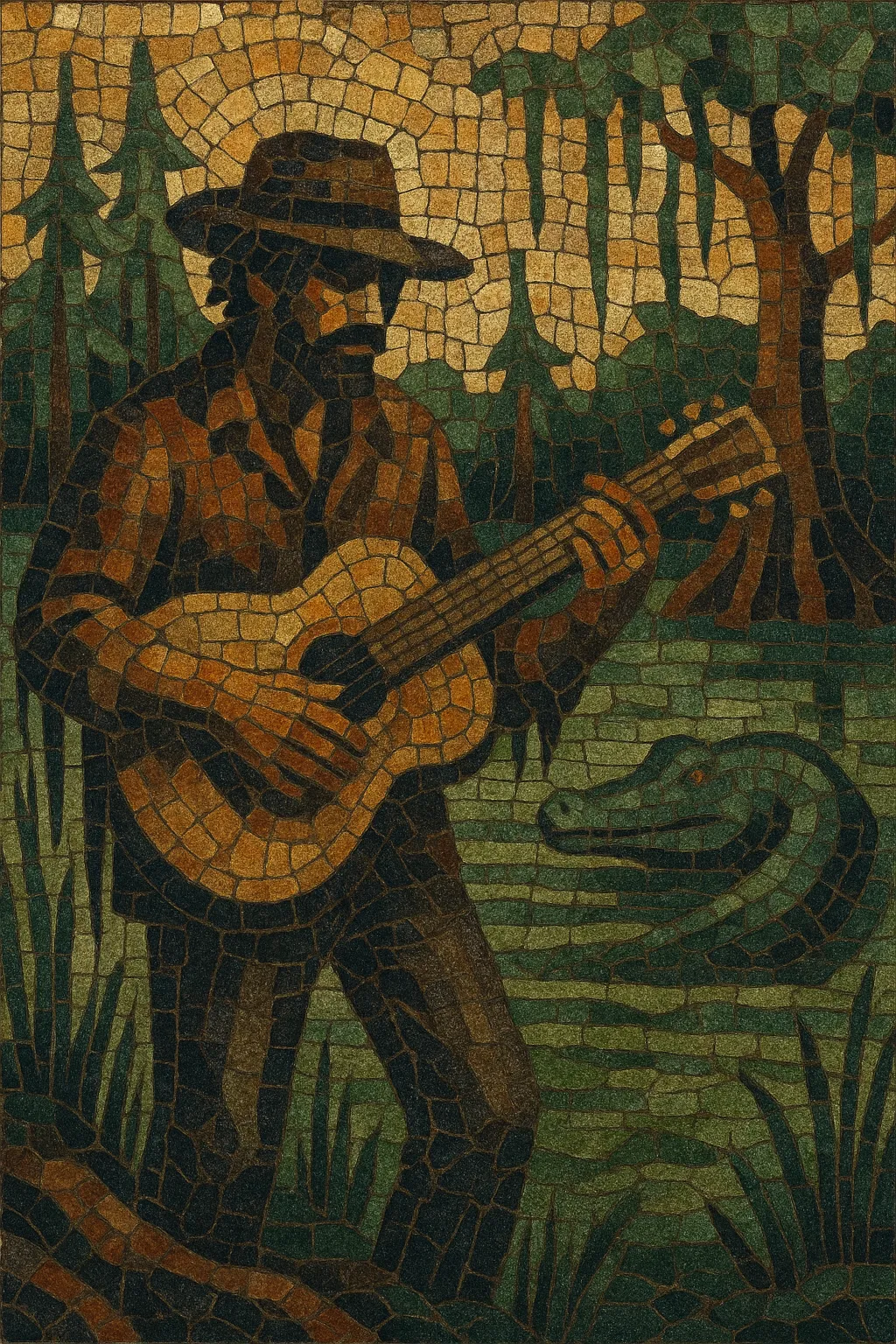

Swamp rock is a gritty, rootsy form of rock that evokes the humid atmosphere of the U.S. Gulf Coast. It blends the loping rhythms and minor-key moods of Louisiana swamp blues with rock and roll drive, country earthiness, and New Orleans R&B grooves.

Characterized by tremolo‑soaked electric guitars, thick reverb, hypnotic mid‑tempo grooves, and warm Hammond organ or piano, the style favors simple, blues-based progressions and storytelling lyrics. Songs often reference bayous, backroads, voodoo lore, and the heat and haze of Southern life, creating a sound that feels both murky and magnetic.

Swamp rock’s roots lie in the Louisiana and Southeast Texas ecosystems where swamp blues (Excello artists like Slim Harpo and Lazy Lester) met New Orleans rhythm & blues and Cajun/zydeco dance music. The region’s studio culture, bar bands, and second‑line grooves shaped a distinctive rhythmic feel. By the mid‑1960s, rock and roll bands began amplifying these elements, keeping the bluesy DNA but leaning into electric guitar bite and atmospheric production.

The sound coalesced at the end of the 1960s. Tony Joe White’s 1969 hit “Polk Salad Annie” established the template: tremolo guitar, swampy groove, and Southern storytelling. Creedence Clearwater Revival—though Californian—popularized a mythic bayou aesthetic on albums from 1968–1970, infusing rock with swamp blues cadence and imagery. Dr. John’s Gris‑Gris (1968) brought voodoo psychedelia, funk, and New Orleans mystique into the mix, broadening swamp rock’s palette.

Through the 1970s, Little Feat and The Band folded swamp textures into roots rock and Americana, while Gulf Coast acts such as The Radiators kept a live, jam‑leaning swamp feel. The sound informed the rise of Southern rock and country rock, and it lingered in heartland rock’s unvarnished storytelling and grooves. Periodic revivals surfaced as artists pursued raw, analog, and regionally rooted aesthetics.

Modern torchbearers like JJ Grey & Mofro helped reassert swamp rock’s identity in the 2000s, emphasizing atmospheric guitars, humid grooves, and bayou narratives. The genre’s influence remains audible in Americana, alt‑country, and Southern rock—anywhere gritty guitars, hypnotic mid‑tempos, and Southern gothic themes converge.

Use tremolo‑capable electric guitars (Telecaster/Strat) through tube amps with spring reverb and amp tremolo. Add Hammond B‑3 or electric piano for sustained chords and swampy pads. Include a tight rhythm section (warm, deadened drums; round, supportive bass) and occasional harmonica or slide guitar. Accordion or fiddle can nod to Cajun/zydeco roots.

Aim for mid‑tempo, loping feels (often straight eighths with behind‑the‑beat snare). Borrow second‑line and New Orleans R&B syncopation; keep the pocket hypnotic rather than busy. Ghost notes on snare and lightly swung hi‑hats add grease.

Favor simple, blues‑based forms (I–IV–V, minor‑pentatonic riffs) and modal inflections (Mixolydian for a rootsy lift, natural minor for shadow). Riffs should be economical, repetitive, and drenched in tremolo/reverb. Melodies are conversational and gritty, with a Southern drawl or relaxed phrasing.

Tell concise stories about rural Southern life: bayous, backroads, storms, creeks, Spanish moss, and folklore (voodoo, hoodoo). Keep language plainspoken and evocative, mixing toughness with melancholy. Refrains should be memorable and mantra‑like.

Track live where possible to capture room bleed and humidity. Use tape‑style saturation, plate/spring reverbs, and tremolo as tone shapers, not ornaments. Leave space: two or three guitar parts max (riff, fills, occasional slide), organ pads, and a steady rhythm section. Prioritize feel over precision; slight looseness adds authenticity.