Slovak folk music is the traditional music of the Slovak people, shaped by rural life in the Carpathians and the country’s borderland exchanges with neighboring Slavic and Central European cultures.

It features distinctive regional styles (e.g., Terchová, Liptov, Detva, Šariš, and Zemplín), multipart choral singing, and lively dance repertoires such as polka, karička (circle dance), odzemok (a virtuosic men’s dance), and the variable-tempo čardáš. Melodies often employ modal colors (Dorian, Mixolydian), drones, and heterophony, while rhythms emphasize bouncing two-steps, heel-toe patterns, and offbeat accompaniment.

Characteristic instruments include the fujara (a monumental overtone fipple flute inscribed by UNESCO), koncovka (end-blown flute), gajdy (bagpipes), heligónka (diatonic button accordion), cimbalom (hammered dulcimer), violin family in the classic ľudová hudba string-band setup (primáš/lead violin, kontra/three-string viola, and contrabass), and occasional clarinet. Lyrics range from love and wedding songs to shepherd, recruiting, and outlaw ballads (e.g., tales linked to Jánošík), sung in vivid local dialects.

Traditional Slovak song and dance practices grew from agrarian and pastoral life, especially in the mountains and valleys of the Western and Eastern Carpathians. Shepherds developed unique aerophone traditions (fujara, koncovka) and drones, while village life fostered communal circle dances, call-and-response refrains, and seasonal/ritual repertoires (harvest trávnice, wedding songs, carols).

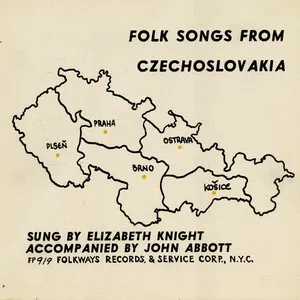

During the 1800s, the Slovak national revival helped crystallize a shared identity around folk song. Collectors, poets, and early composers documented melodies and texts, shaping canons that influenced art music and education. Cross-border exchanges with Czech, Polish, Hungarian, and Rusyn communities enriched the repertoire, as shared dances and band formats spread across the region.

After World War II, professional ensembles standardized and staged folk traditions. Lúčnica (founded 1948) and SĽUK (1949) created touring programs with choreographed dances and polished string-band/cimbalom arrangements, broadcasting Slovak folk aesthetics at home and abroad. Filmmakers and ethnomusicologists (e.g., Karol Plicka) preserved field recordings, while festivals such as Východná, Detva, and Myjava became vital hubs for transmission.

UNESCO inscriptions further highlighted emblematic practices: the fujara and its music (originally proclaimed in 2005), the Terchová music tradition (2013), and the bagpipe culture of Slovakia (2015).

Since the 1990s, a vibrant scene of village bands, regional folklore ensembles, and modern groups has renewed the music both authentically and through fusion. Young primáš-led string bands, cimbalom-based lineups, and singer‑collectors collaborate with world‑music, folk‑rock, and chamber‑folk projects, keeping dialects, styles, and dance repertoires alive on stages, recordings, and community events.

Decide on a locality (e.g., Terchová, Liptov, Šariš, Zemplín) and let its dance types, dialect, and typical band setup guide your piece. Reference local tempo feels (e.g., elastic čardáš or buoyant polka) and vocal practices (solo ballad vs. multipart chorus).

Use a ľudová hudba string band: primáš (lead violin) for melody, kontra (three‑string viola) for harmonic offbeats (I–V dyads and modal color tones), and contrabass for strong‑beat grounding. Add cimbalom for rolling arpeggios and countermelodies, heligónka (diatonic button accordion) for rhythmic pulses, and clarinet for piercing ornaments. For pastoral colors, feature fujara or koncovka over a sustained drone; gajdy (bagpipes) add nasal timbre and rhythmic bark.

Base dances in 2/4 with a springy two‑step and accented offbeats (polka, karička). For čardáš, begin slower and accelerate to a brisk finish, keeping phrasing elastic. Men’s dances like odzemok favor punchy accents, foot-stomps, and breaks. Typical song forms are strophic with refrains; arrange medleys that cycle through related tunes and keys as in live dance sets.

Favor modal palettes (Dorian, Mixolydian, Aeolian) and drones (often on D or A). Keep harmonic rhythm simple: I–V and occasional bVII or IV color tones. The kontra supplies offbeat triads/dyads; avoid heavy functional progressions. Let the cimbalom fill inner voices with broken‑chord figurations and cross‑rhythms.

Write singable, narrow‑range tunes with motivic repetition and call‑and‑response phrases. Embellish with turns, slides, grace notes, and appoggiaturas. On fujara/koncovka, exploit the overtone series for natural harmonics; on violin, use double‑stops and open‑string drones. Multipart female choruses can sing parallel thirds/sixths or heterophonic variants for a rich village texture.

Lyrics dwell on love, weddings, recruiting/soldier stories, shepherd life, seasons, and local heroes (e.g., Jánošík). Use the region’s dialect and punctuate cadences with interjections (e.g., “hej!”, “hopa!”). Keep verses compact and easily repeatable for dance.

Structure sets around dance flow: start with a vocal strophic song, segue to instrumental dance tunes, then accelerate. Emphasize groove: bass on downbeats, kontra on offbeats, cimbalom weaving. Record with minimal miking to capture room blend and stomps; prioritize the primáš and lead vocal while preserving ensemble heterophony.