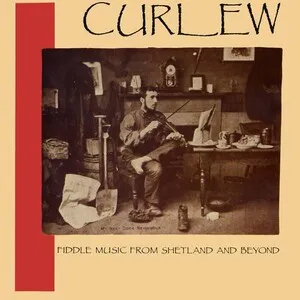

Shetland & Orkney folk music is the fiddle‑led traditional music of Scotland’s far‑northern isles, where Scottish dance forms meet strong Nordic (especially Norwegian) influences. Tunes are typically brisk reels and jigs, buoyant waltzes and polkas, and lyrical slow airs, all shaped by a distinctive “ringing‑strings” approach that favours open‑string drones, double stops, and bright, bell‑like resonance.

While sharing forms with mainland Scottish traditions (reels, jigs, strathspeys), the island styles differ in feel: Shetland playing is often more driving and exuberant, with powerful bowing and propulsive rhythm suited to lively dance. Orkney performance often leans to warm harmonies, graceful waltzes, and melodic airs, reflecting the archipelago’s seafaring and Nordic heritage. Guitar (in a swing‑coloured local style), piano, accordion, and mandolin commonly accompany the fiddle, and modern ensembles range from intimate duos to fiddle sections in festival bands.

The repertoire mixes old “trowie” (fairy) tunes and local dance music with modern island compositions that have travelled widely across the folk world. Two of the UK’s best‑known folk festivals—the Shetland Folk Festival and the Orkney Folk Festival—help sustain and evolve the tradition.

Fiddling reached Shetland and Orkney by the 1700s, merging older local song and dance with imported Scottish reels, jigs, and strathspeys. Centuries of Norse contact left a lasting imprint on bowing, ornamentation, and modal flavour. Community dances in halls and kitchens sustained an ear‑led, social tradition, where players learned face‑to‑face and adapted repertoire to local steps and spaces.

Strathspey and reel societies, house dances, and local bands formalised and spread island repertoire. Accompaniment gained importance: piano and accordion became common, and in Shetland a distinctive swing‑tinged guitar backing (later associated with Peerie Willie Johnson) developed alongside the dominant fiddle.

From the 1950s–1970s, figures such as Tom Anderson documented and taught the Shetland style, composing enduring tunes (e.g., “Da Slockit Light”). Aly Bain’s national and international prominence helped move island music onto concert stages and broadcasts, coinciding with the wider British/Scottish folk revival. Orkney’s scene flourished through community teaching and ensembles, leading to a new generation of performers and composers.

Since the 1980s, the Shetland Folk Festival and Orkney Folk Festival have been crucial hubs. Bands like Fiddlers’ Bid, and artists such as Chris Stout and Kevin Henderson, globalised island idioms, while Orkney outfits (The Wrigley Sisters, Fara, Saltfishforty) foreground rich harmony and new compositions. Today, workshops, schools, and sessions keep transmission strong, and island tunes are standard repertoire in Celtic and international sessions.