Sahrawi music is the modern and traditional music of the Sahrawi people of Western Sahara and the refugee camps across the border in Algeria. It blends Bedouin-Hassaniya poetic traditions and modal melodies with hand-drum grooves, call-and-response vocals, and (in contemporary practice) electric guitar textures.

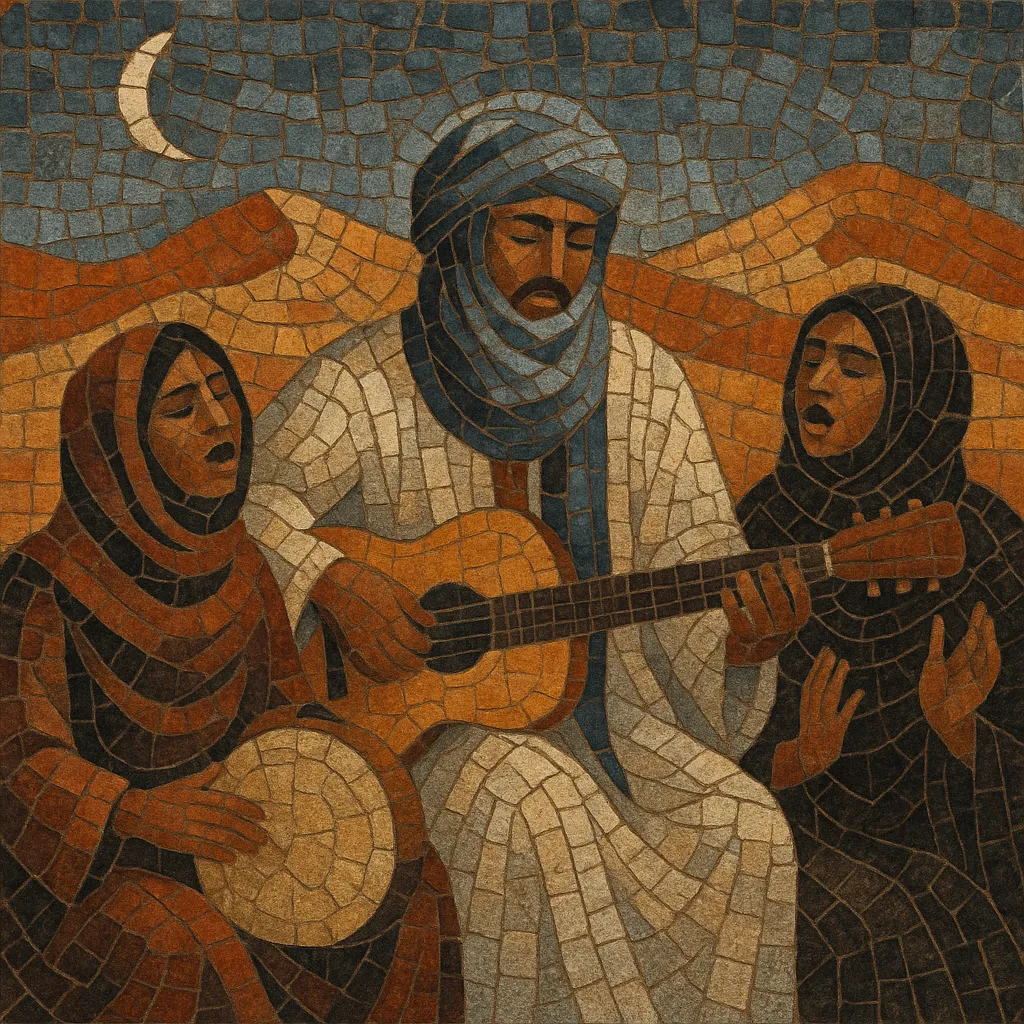

At its core are the tbal (frame drum), communal female choruses with ululations, and solo vocal lines that carry richly metaphorical poetry about desert life, love, exile, and political struggle. Since the late 1970s, musicians have adapted the timbre and phrasing of older instruments like the tidinit (lute) and ardin (harp) to the electric guitar, creating cyclical, trance-like riffs over swaying 6/8 and 12/8 rhythms.

The result is a sound that feels both intimate and epic: rooted in Hassaniya verse and North African maqam-like modes, yet energized by amplified guitars and a resilient, communal performance ethos shaped by displacement and resistance.

Sahrawi music grows out of the Hassaniya Arab Bedouin traditions of the western Sahara. Poetic recitation and sung verse were central to social life, with accompaniment from instruments such as the tidinit (lute) and ardin (harp), and rhythmic support from the tbal hand drum. Modal melodies, ornamented vocal delivery, and antiphonal singing were common.

During the Spanish colonial period (late 19th century–1975), Sahrawi musical practices remained largely community-based and oral. Radio exposure to Maghrebi and Arabic music increased, but documentation was limited. The poetic repertoire (themes of love, honor, the desert, and clan history) continued to frame musical performance.

Following Spain’s withdrawal and the onset of war, large numbers of Sahrawis settled in refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria. In these camps, music took on an explicitly communal and political role—preserving identity, telling histories, and boosting morale. Musicians began adapting the idioms of the tidinit and ardin to electric guitar and bass, while the tbal and women’s chorus remained central. Low-cost cassette production helped circulate songs across camps and diaspora.

Labels and cultural organizations in the 1990s (notably Nubenegra) helped bring Sahrawi artists to wider audiences. This period produced international releases that defined the modern Sahrawi electric sound: cyclical guitar figures, modal vocal lines, and steadfast 6/8/12/8 grooves.

Artists like Mariem Hassan and Aziza Brahim toured internationally, solidifying the genre’s profile. Groups such as Group Doueh showcased raw, amplified desert textures, while ensembles like Tiris and El Wali documented the camp-based repertoire. Contemporary recordings vary from spare voice-and-tbal formats to full electric bands with keyboards, but core features—Hassaniya poetry, call-and-response, ululations, and propulsive hand-drum rhythms—remain intact. The sound now dialogues with broader North African, Saharan, and "desert blues" scenes, while continuing to serve as a living chronicle of Sahrawi experience.