Rembetika (Rebetiko) is the urban Greek popular music that crystallized in port cities such as Piraeus in the early 20th century, especially after the 1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe and the influx of refugees from Smyrna/Izmir and other Ottoman centers.

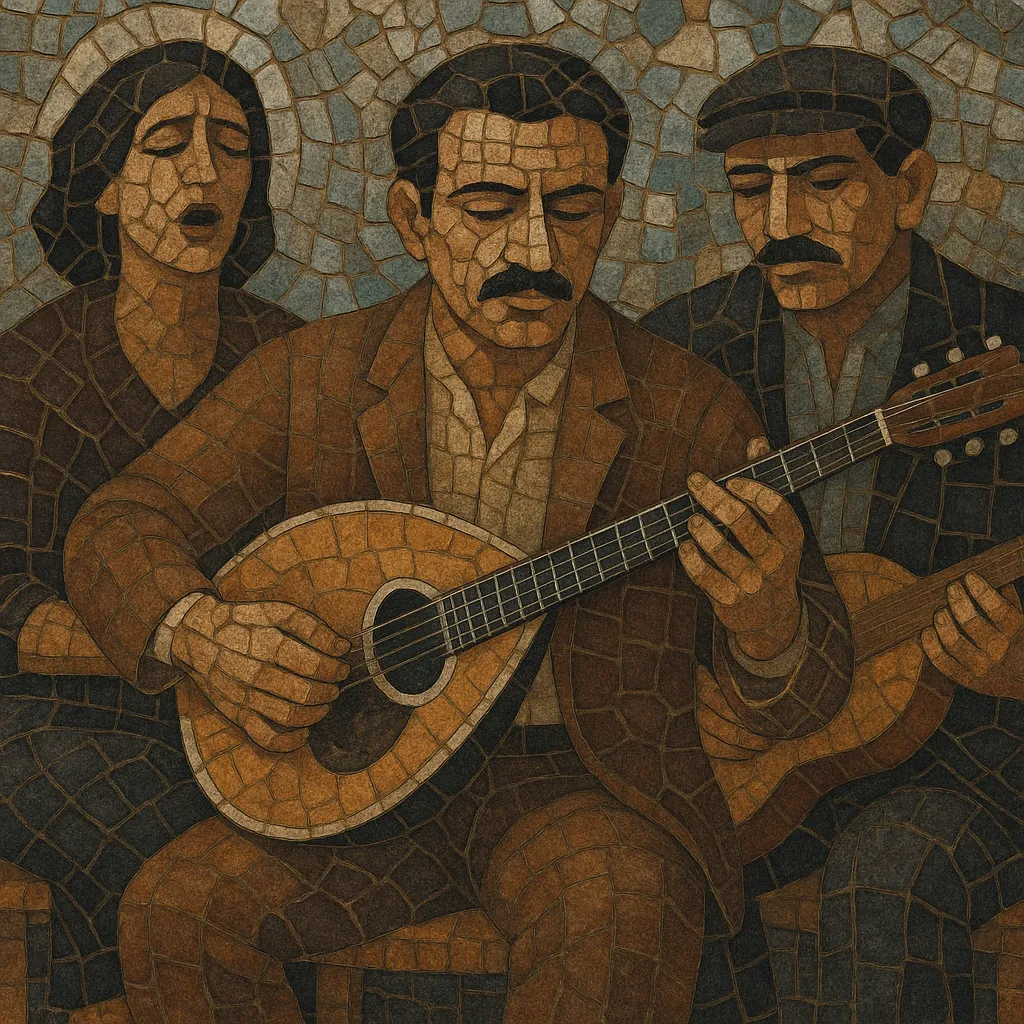

It features modal melodies (dromoi) derived from the Ottoman/Turkish makam system, expressive vocal delivery, and small ensembles centered on bouzouki, baglamas, and guitar, with occasional violin, oud, or santouri. Core dance rhythms include zeibekiko (9/8), hasapiko (2/4 or 4/4), and tsifteteli (4/4), typically performed at intimate tempos with ornamented lines and a prominent improvised taximi (taksim) introduction.

Lyrics explore love, exile, poverty, prison life, hashish dens, and the codes of the urban underworld, giving the style a gritty, blues-like ethos that is nevertheless distinctly Greek and Eastern Mediterranean.

Rembetika took shape among Greek-speaking communities in late Ottoman urban centers and crystallized in Greece in the 1920s. The 1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe brought waves of refugees to port cities like Piraeus and Thessaloniki, carrying café-amán repertory, instruments, and modal practice. Street and café musicians fused this with local dimotiko traditions, forming a new urban song idiom.

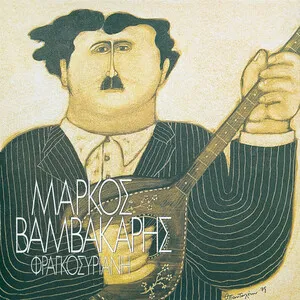

By the early–mid 1930s, a distinct “Piraeus school” coalesced around bouzouki and baglamas. Figures like Markos Vamvakaris, Giorgos Batis, and their circles set the archetype: modal taximia, zeibekiko rhythms, and hard-edged lyrics about working-class life and the manges subculture. Recording technology and burgeoning record markets helped spread the sound.

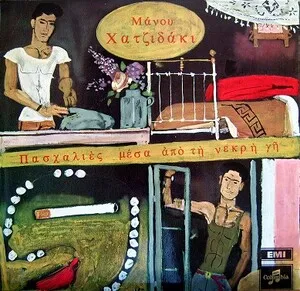

The Metaxas dictatorship (1936–1941) imposed censorship, curbing explicit underworld and hashish references and pushing cleaner diction and themes. World War II and the Greek Civil War disrupted musical life, but composers such as Vassilis Tsitsanis reshaped rembetika toward a more refined, widely acceptable style that laid the foundation for laïko.

As postwar laïko rose, classic rembetika receded from the mainstream, yet a significant revival began in the 1970s through reissue programs, scholarship, and new performances that honored the old repertoire. Today, rembetika is recognized as a cornerstone of modern Greek popular music, performed globally and studied for its intercultural, modal, and poetic richness.

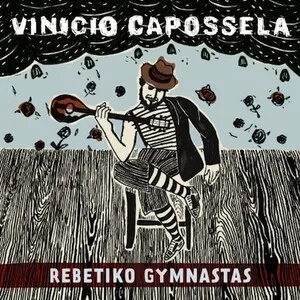

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)