Rajasthani folk music is a centuries-old musical tradition from the desert state of Rajasthan in northwestern India. It is known for powerful, ornamented vocals, modal melodies related to ragas (especially the regional Maand mode), and propulsive dance rhythms. Songs celebrate love, monsoon rains, heroic epics of Rajput valor, and devotional themes addressed to Krishna, local deities, and Sufi saints.

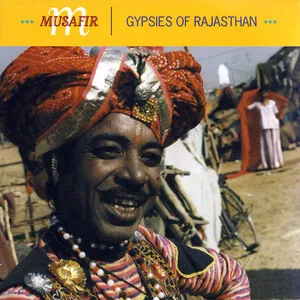

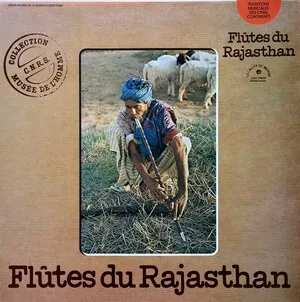

The style is carried by hereditary communities such as the Manganiyar and Langa, temple bards and storytellers like the Bhopa, and dance traditions including the Kalbeliya. Signature instruments include the kamaicha (bowed lute), ravanhatta (spike fiddle), sarangi, algoza (double flute), morchang (jaw harp), bhapang (talking drum), khartal (castanet-clappers), dholak, and harmonium. Performances range from intimate ballad recitations to high-energy dance songs (e.g., ghoomar), often featuring call-and-response and trance-like grooves.

Rajasthani folk music grew from bardic, devotional, and community song practices that predate modern history, reaching recognizably classical form by the 18th century under Rajput court patronage. Court musicians helped crystallize the Maand mode and elevated performance practices, while village traditions continued to nurture work songs (panihari), wedding repertoires, seasonal pieces, and ritual/devotional genres.

Hereditary musician communities—the Manganiyar and Langa—preserved extensive repertoires, performing for patrons across Hindu and Muslim households. The Bhopa-Bhopi tradition performs epic narratives such as Pabuji ki Phad with ravanhatta accompaniment before painted scrolls. Kalbeliya musicians energized dance-oriented songs with morchang, dholak, and fast clapping patterns, contributing a distinct stage aesthetic.

Iconic timbres come from the kamaicha and ravanhatta’s resonant, nasal bowing; the bright chatter of khartal; the twang of morchang; and breathy, reedy lines on algoza. Vocals feature microtonal slides (meend), oscillations (andolan), and robust chest-tone projection. Cyclical rhythms favor folk adaptations of tāla like keherwa (8), dadra (6), and rupak (7), aligned with dance forms and celebratory contexts.

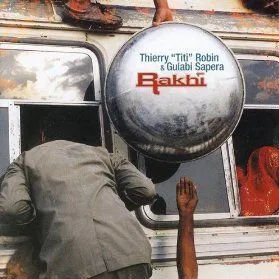

From mid-20th century radio and gramophone recordings to late-20th/early-21st century world-music circuits, Rajasthani folk gained national and international audiences. Artists toured globally, and festivals such as Jodhpur RIFF brought collaborations with jazz, electronica, and global folk. Bollywood/filmi composers frequently drew on Rajasthani melodies and rhythms, embedding the style in mainstream Indian soundtracks while grassroots traditions remain vital in ceremonies and local patronage systems.