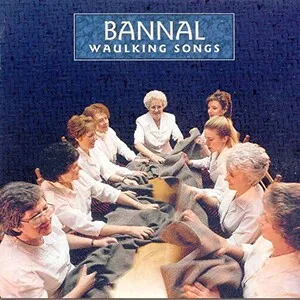

Òrain luaidh are traditional Scottish Gaelic waulking songs, sung in the Highlands and Hebrides during the communal process of fulling (thickening) woven tweed. A lead singer would improvise or deliver narrative verses while a chorus of workers answered with short refrains and vocables, keeping time as the cloth was rhythmically beaten on a table.

The genre is defined by strong, steady pulse; call-and-response structure; repetitive refrains with non-lexical syllables (e.g., “hi o hò u iù”); and modal, pentatonic-leaning melodies with narrow to moderate range. Themes range from love and local history to satire and laments, reflecting everyday life in Gaelic-speaking communities. Traditionally unaccompanied, the primary “instrumentation” was the percussive thud and clap produced by waulking itself.

Òrain luaidh emerged as communal work songs in Gaelic-speaking Scotland, especially the Hebrides, where women waulked (fulled) freshly woven tweed. The practice likely crystallized in the early modern period, with elements rooted in older Gaelic oral song traditions. The songs’ purpose was practical: to coordinate collective labor, pace the strenuous task, and alleviate fatigue through shared rhythm and storytelling.

A soloist (often experienced in local repertoire) led improvised or semi-improvised verses, answered by a group refrain. Non-lexical vocables ensured consistent rhythm and easy participation, while modal melodies (often Dorian or Mixolydian) and a steady duple or compound meter matched the physical motions of waulking. Lyrics frequently referenced local people and places, historical events, romantic narratives, and occasionally playful or risqué humor.

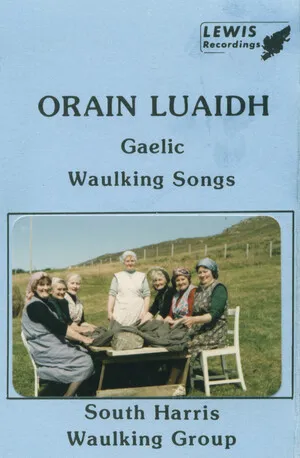

As industrialization and changing textile practices reduced domestic waulking, the functional context declined in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Folklorists and field collectors—alongside commercial 78 rpm recordings and later radio/TV—preserved many variants, capturing both lyrics and performance practice across islands like Barra, Uist, and Lewis.

The late-20th-century folk revival brought waulking songs to stages and recordings, often performed unaccompanied or with subtle accompaniment. Artists and ensembles recontextualized òrain luaidh for listening rather than labor, while some community events still reenact waulking as cultural heritage. Modern adaptations range from faithful traditional delivery to innovative, globally influenced arrangements that retain the call-and-response heartbeat of the genre.