Your digging level for this genre

Description

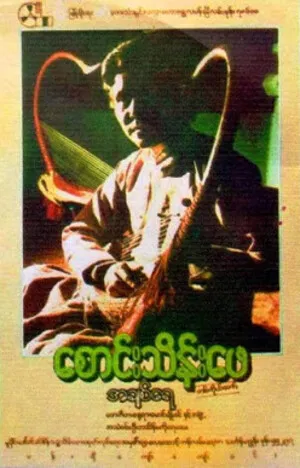

Mono (monaural) is not a stylistic genre but a recording and playback format in which all audio is captured and reproduced through a single channel. In practice, it shaped how music was arranged, recorded, mixed, and heard for most of the 20th century, especially on shellac 78s, early LPs, 45 rpm singles, AM radio, and motion picture sound.

Because there is no left/right image, mono emphasizes clarity, midrange punch, and balance within one point source. Classic mono mixes were often made separately from stereo, yielding tighter vocals, more focused rhythm sections, and a cohesive "centered" sound that translates well on small speakers and public-address systems. Many cornerstone blues, jazz, pop, R&B, rock ’n’ roll, and early rock records were conceived with mono in mind, making its sonic signature historically and aesthetically significant.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)