Manzuma is an East African Islamic devotional singing tradition associated especially with the Muslim communities of Harar and eastern Oromia in Ethiopia. The word itself derives from the Arabic manẓūma (poem set in verse), and the practice centers on strophic praise-poems for the Prophet Muhammad, pious supplications, and moral instruction.

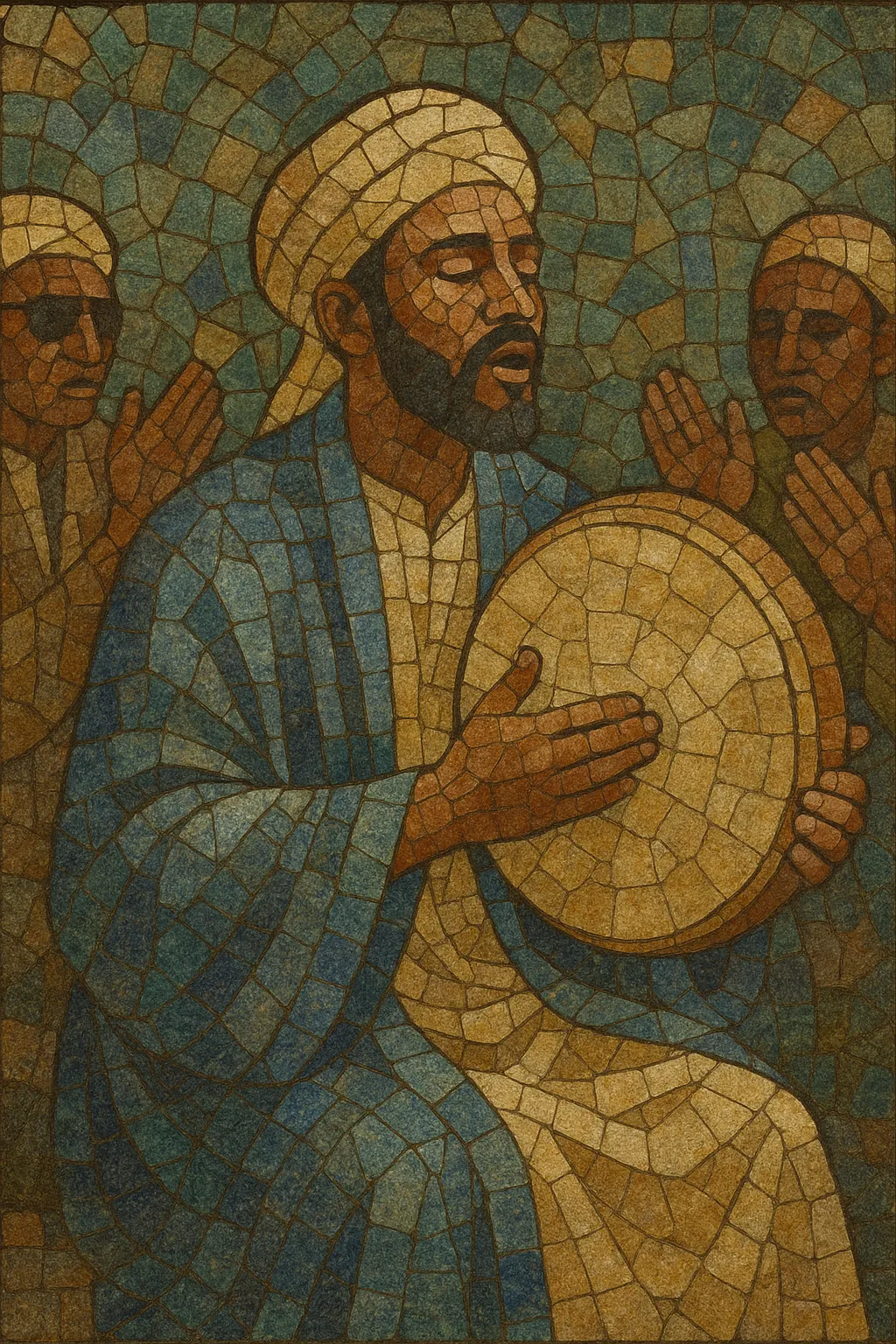

Musically, manzuma blends Arabic maqām-informed melodic sensibilities with local Ethiopian aesthetics. It is typically delivered by a unison or call-and-response chorus led by a precentor (munshid) and supported by frame drum (duff) patterns, handclaps, and antiphonal responses. Performances occur at mawlid celebrations, religious gatherings, weddings, and community events, and are commonly sung in Harari, Oromo, and Arabic. The overall sound is fervent yet gentle—devotional, rhythmically buoyant, and text-forward.

Manzuma took shape in the 1800s in and around the holy city of Harar, where long-standing trade and scholarly ties with the Arabian Peninsula facilitated the circulation of Arabic poetry, religious pedagogy, and melodic ideas. Local Muslim scholars adapted Arabic panegyric verse into performative, strophic songs for communal devotion, anchoring the practice in Sufi-oriented gatherings and the celebration of the Prophet’s birthday (Mawlid).

In the early-to-mid 20th century, manzuma spread more widely across eastern Ethiopia through religious schools, traveling scholars, and urbanization (Harar, Dire Dawa). Ensembles standardized call-and-response formats, duff-accompanied rhythms, and repertories of well-known praise poems. While strongly rooted in piety, manzuma also served social functions—teaching ethics, strengthening communal identity, and marking life-cycle ceremonies.

From the late 20th century onward, cassette tapes, local radio, and later digital platforms enabled broader circulation of manzuma recordings. Community ensembles continue to perform at religious events, sometimes integrating microphones, harmonized choral arrangements, and carefully paced duff ostinati. Despite modernization, the genre’s core features—devotional texts, collective participation, and melodic contours informed by Arabic maqām alongside Ethiopian idioms—remain central.