Maftirim is a paraliturgical Jewish choral tradition that flourished among the Ottoman Empire’s Sephardi communities, especially in Edirne, Istanbul, and İzmir. It sets Hebrew piyyutim (liturgical poems) to the modal and rhythmic language of Ottoman/Turkish classical music (makam and usul).

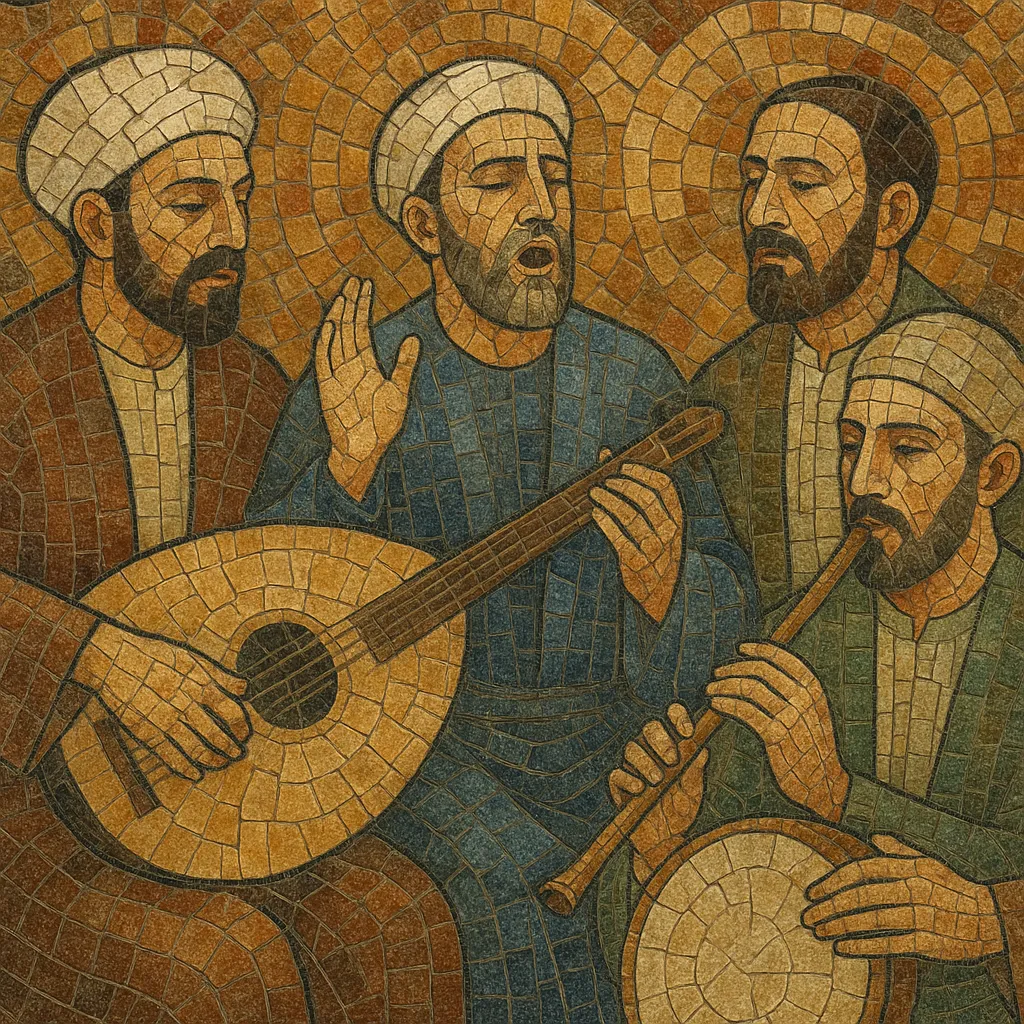

Typically performed by male choirs of hazzanim (cantors) and lay singers, Maftirim pieces are sung a cappella in synagogue contexts (in keeping with Sabbath restrictions) and often feature a leader–chorus format, melismatic ornamentation, and heterophonic unison textures. Outside of strictly liturgical settings, the same repertoire may be arranged with Ottoman instruments such as oud, tanbur, ney, kanun, keman, and frame drums.

Musically, Maftirim bridges Hebrew sacred poetry and the aesthetics of Ottoman court and Sufi repertoire, using characteristic makams (e.g., Hicaz, Uşşak, Hüseyni, Rast, Segâh) and usul cycles (e.g., Sofyan, Aksak/Yürük semai). The result is a contemplative and refined devotional sound that stands at the crossroads of Jewish liturgy and Ottoman art music.

Maftirim emerged in the 1600s within the Jewish communities of the Ottoman Empire, particularly in Edirne, then an important cultural center. Sephardi Jews—descendants of Iberian exiles—adapted Hebrew piyyutim to the modal vocabulary of Ottoman classical music. Contacts with court musicians and Sufi circles (especially Mevlevi aesthetics) shaped a uniquely Jewish, yet deeply Ottoman, devotional sound.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, Maftirim choirs were active in Edirne, Istanbul, and İzmir. Ensembles developed repertories aligned with makams and usul cycles, often structuring suites that mirrored Ottoman fasıl logic in a synagogue-appropriate, a cappella idiom. A leader–chorus practice, extensive melisma, and microtonal nuance became signature traits.

Political upheavals, migration, and modernization reduced the number of active Maftirim circles in the early–mid 20th century. Nevertheless, renowned Ottoman-Sephardi hazzanim and musicians documented, transmitted, and recorded aspects of the tradition, preserving melodies and performance practice for later generations and scholarship.

From the late 20th century onward, ethnomusicological work and community-based projects in Turkey and the diaspora prompted renewed interest. Modern choirs and collaborations with Ottoman art-music ensembles have revived Maftirim pieces in concert and recording contexts, while synagogue performance remains a cappella and devotional.