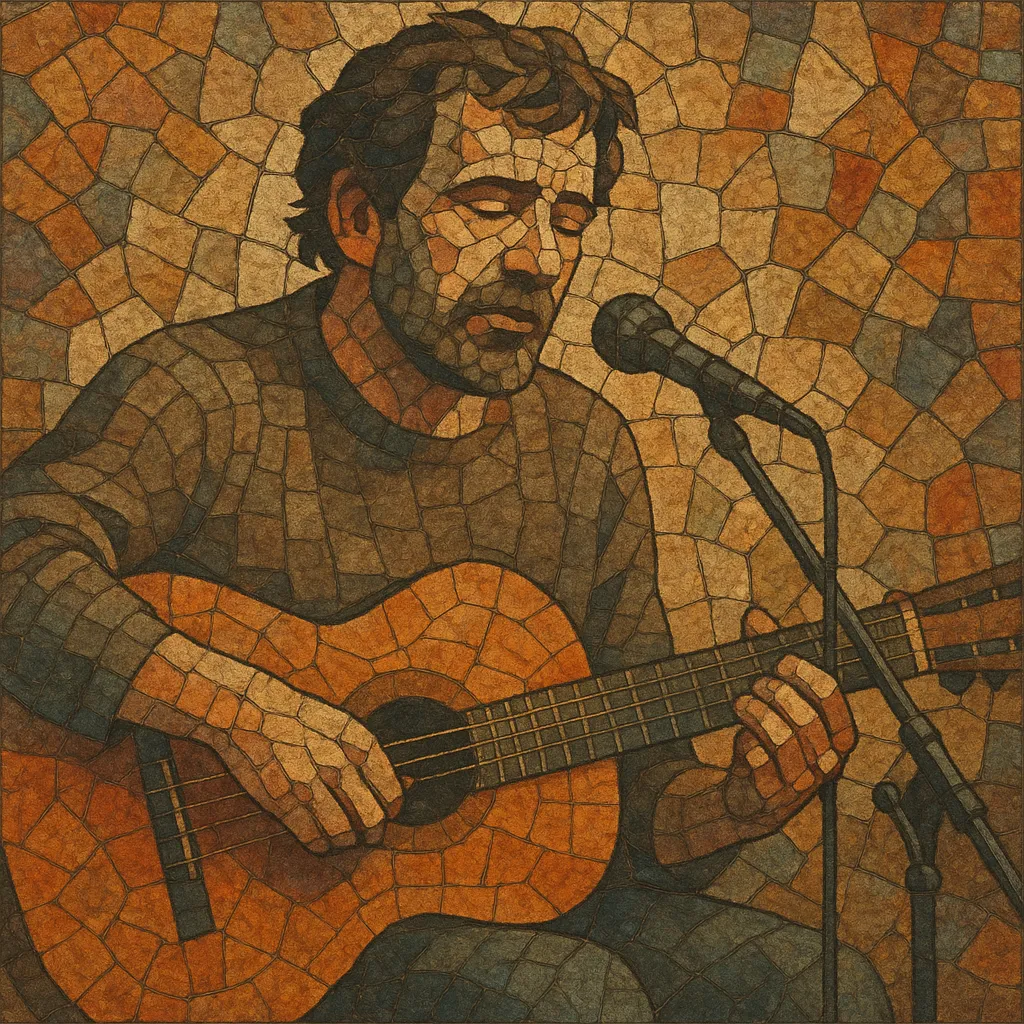

Liedermacher is the German-speaking singer‑songwriter tradition that foregrounds text, storytelling, and social commentary. Songs are typically performed with solo voice and acoustic guitar or piano, prioritizing clarity of diction and the semantic weight of each line over virtuosic display.

Stylistically, it sits at the crossroads of folk balladry, cabaret, and French‑style chanson: intimate, literary, and often political. Themes range from protest and satire to tender portraits of everyday life, introspection, and love—frequently delivered with irony or wry humor. The arrangements are generally sparse, keeping the focus on lyrics and performance.

Liedermacher emerged in West Germany in the 1960s student and protest movements and had parallel, more constrained developments in the GDR, where censorship shaped tone and metaphor. Its legacy is a durable culture of German‑language songcraft that continues to influence indie, pop, and even hip hop.

In West Germany, Liedermacher crystallized in the 1960s amid student movements and a broader folk revival. The Burg Waldeck festivals (mid‑1960s) became a focal point, showcasing artists like Franz Josef Degenhardt, Hannes Wader, and Reinhard Mey. Musically and poetically, they drew on American protest folk and French chanson while retaining German poetic cadence and cabaret’s satirical bite. The term “Liedermacher” (literally “song‑maker”) emphasized craft, authorship, and textual primacy.

In the GDR, the tradition developed under stricter cultural oversight. Wolf Biermann’s critical songs led to censorship and expatriation in 1976, a defining moment that underscored the political stakes of the genre. Nevertheless, songwriters such as Bettina Wegner, Gerhard Schöne, and later Gerhard Gundermann cultivated a metaphor‑rich, often allegorical Liedermacher voice under the Amiga label and in small venues.

The 1970s brought wider recognition: Konstantin Wecker fused piano‑driven chanson with jazz inflections; Wader and Mey refined the classic guitar‑and‑voice format; Degenhardt codified the political songbook. Arrangements remained intimate but occasionally expanded to small ensembles, with harmony and rhythm borrowing from jazz, bossa, and waltz idioms. In live settings, artists retained cabaret’s tradition of direct audience address and spoken interludes.

Post‑1990, Gundermann’s work bridged East‑West experiences with industrial, working‑class narratives. A new wave—Funny van Dannen among them—adopted a drier, more ironical everyday tone. Liedermacher aesthetics seeped into rock and pop, and small clubs and song‑circles continued to be the genre’s lifeblood.

A contemporary generation (e.g., Dota Kehr, Sarah Lesch) reanimated the form with topical lyrics, indie‑folk textures, and DIY production, while festivals and house concerts maintained its intimate ethos. The genre’s literate lyricism has influenced German indie and singer‑songwriter pop and informed the narrative and satirical traditions in German hip hop.

Liedermacher established a durable, German‑language approach to songwriting that treats lyrics as literature set to music. Its blend of folk simplicity, cabaret wit, and chanson poetics remains a reference point for artists seeking clarity of voice, social engagement, and intimacy.

Start with voice plus acoustic guitar or piano. Keep arrangements sparse (occasional double bass, accordion, violin, or light percussion) so lyrics stay central. Favor intimate dynamics and close‑miked vocals.

Use diatonic progressions (I–IV–V, ii–V–I), with tasteful modal interchange or borrowed chords for color. Minor keys suit reflective or political material; simple, singable melodies help audience connection. Piano‑based songwriting can incorporate gentle jazz extensions (add9, maj7, m7b5) without obscuring the tune.

Moderate tempos (≈60–110 BPM) in 4/4 or 3/4 are common. Allow rubato at phrase ends to spotlight important lines. Waltz feels and light swing are idiomatic; avoid heavy grooves that distract from the text.

Write in clear, idiomatic German (dialects welcome). Prioritize narrative clarity, vivid imagery, and turns of phrase. Common forms are strophic verses with a recurring refrain. Topics include social critique, political satire, personal reflection, and everyday vignettes. Use irony, understatement, and rhetorical devices (internal rhyme, anaphora, alliteration) to deepen meaning.

Strophic forms work well; add a brief bridge or instrumental interlude for contrast. Build dynamics gradually: solo voice first, then add light accompaniment in later verses. Keep intros/outros short to frame the text.

Articulate consonants and shape phrases as if reading poetry. Employ spoken‑sung passages or brief monologues between songs (a nod to cabaret). Maintain direct eye contact and conversational pacing to foreground the story.

Use minimal processing, natural reverb, and close vocal miking. Avoid dense layering; leave space for words. Recording live in a quiet room often yields the most authentic result.