The Laurel Canyon scene is a late‑1960s to early‑1970s Los Angeles musical movement centered around the hillside neighborhood of Laurel Canyon. Its sound blends folk’s acoustic intimacy with the rich harmonies and amplified jangle of rock, plus a mellow West Coast ease.

Hallmarks include confessional, literate songwriting; stacked vocal harmonies; 12‑string electric shimmer; piano‑led balladry; light, swinging rhythms; and country‑tinged textures like pedal steel. The scene was as much a creative community as a sound—artists lived, wrote, and jammed together, cross‑pollinating ideas that shaped mainstream pop, soft rock, and singer‑songwriter music for decades.

Culturally, it captured California’s post‑Beat, post‑Summer‑of‑Love sensibility: introspective yet sun‑washed, communal yet professionally polished, idealistic but tempered by adult realism.

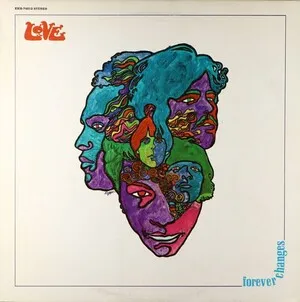

Laurel Canyon, a bohemian neighborhood in the Hollywood Hills, drew a wave of young musicians seeking cheaper rent, close proximity to studios and venues (like the Troubadour and Whisky a Go Go), and a communal, experimental lifestyle. Folk and folk‑rock players—many orbiting The Byrds and Buffalo Springfield—began fusing acoustic songwriting with rock rhythm sections, jangly 12‑string guitars, and tight vocal harmonies. The Mamas & the Papas and Love helped establish Los Angeles as a parallel to the San Francisco psychedelic explosion, but with more songcraft and studio focus.

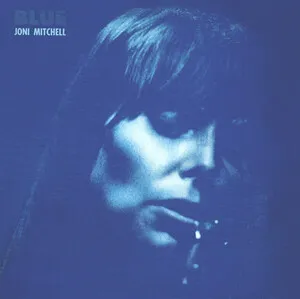

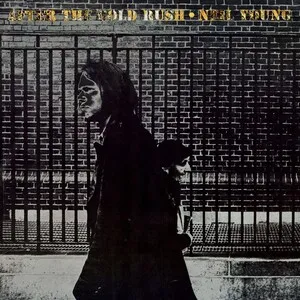

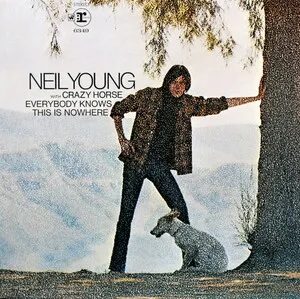

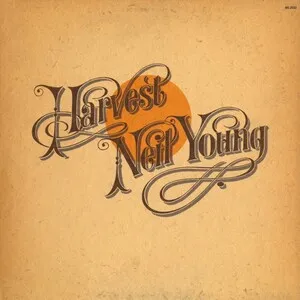

A dense network of houses and informal salons (including Joni Mitchell’s home) nurtured daily collaboration. Out of this came the era’s definitive singer‑songwriter and harmony groups: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young refined intricate multi‑part harmonies and acoustic/electric interplay; Joni Mitchell expanded folk harmony with jazz‑tinged chords and alternate tunings; Carole King translated Brill Building craft into intimate, piano‑led confessionals; Jackson Browne chronicled adult relationships and road‑worn reflection; Linda Ronstadt bridged country, folk, and pop with powerhouse vocals. Industry support (notably Asylum Records and managers like David Geffen) turned the neighborhood’s informal workshops into era‑defining albums.

As country‑rock and soft rock surged, the Eagles emerged (initially from Ronstadt’s band), distilling Canyon harmonies, laid‑back grooves, and pedal‑steel color into radio‑ready songs. Production grew sleeker, edging toward the smoother textures that would later inform yacht rock and adult contemporary. While the communal vibe persisted, success drew artists into bigger studios and broader audiences, gradually dispersing the hyper‑local scene.

The Laurel Canyon aesthetic—intimate storytelling, luminous harmonies, and West Coast warmth—reverberates through jangle pop, indie folk, and the Paisley Underground, and resurfaces in 21st‑century “New Weird America” and California singer‑songwriter revivals. Beyond sound, its collaborative ethos and home‑as‑studio ideal became a lasting blueprint for artist communities.