Kontakion is a long-form hymn of the Byzantine liturgical tradition, typically performed in Greek within the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is a homiletic, narrative chant consisting of a prooimion (introductory stanza) followed by a sequence of metrically identical stanzas called oikoi, all concluding with a common refrain (ephymnion).

Originally the kontakion could comprise dozens of oikoi, forming a poetic-sermonic meditation on a feast, biblical episode, or saint’s life. It is monophonic, modal (set in the eight-mode system, the Octoechos), and text-driven, with a declamatory melodic style that follows the natural accents of the language. In later liturgical practice, most kontakia were reduced to the prooimion (often with one oikos), while the Akathist Hymn preserves the earlier expansive form.

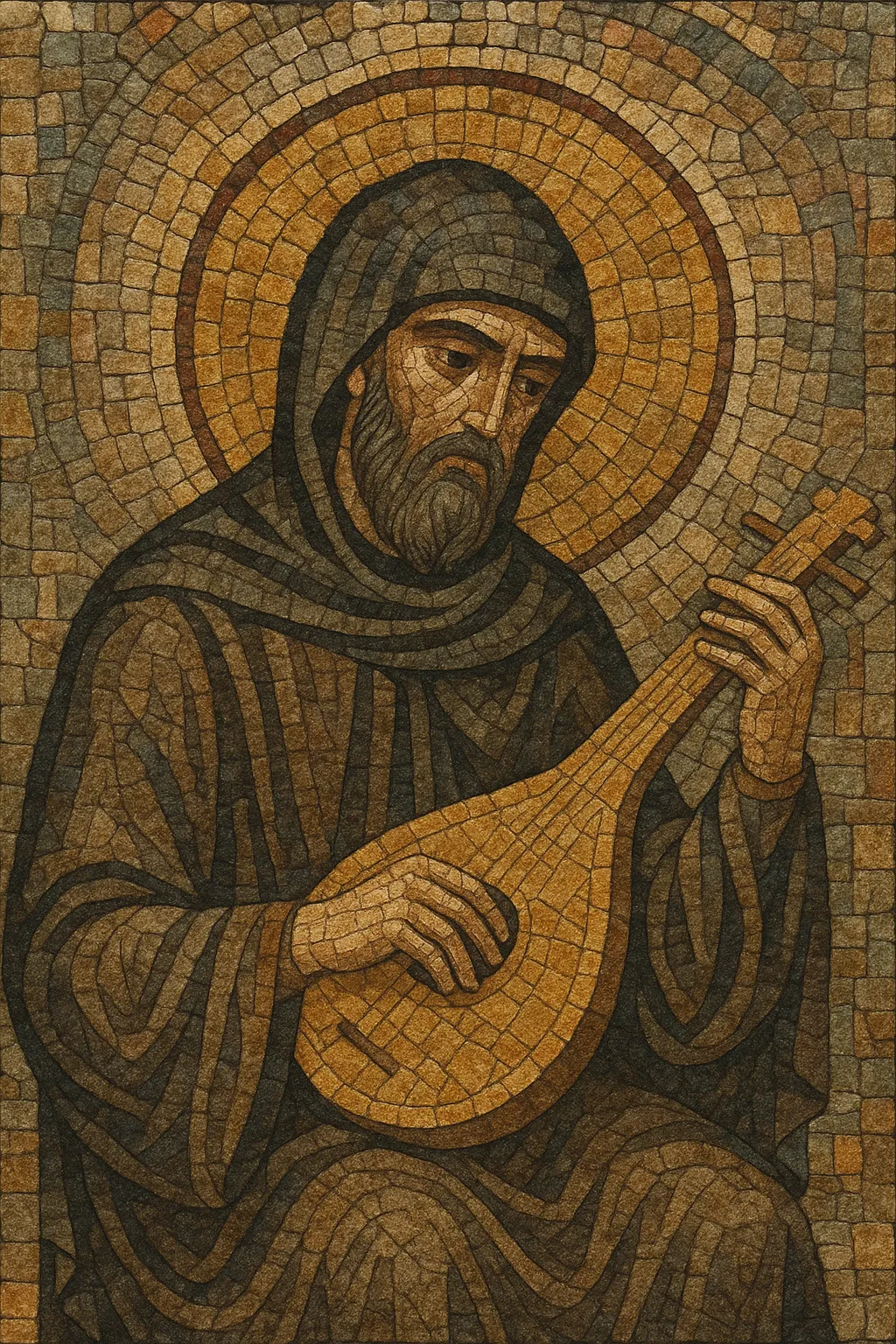

Kontakion emerged in the Byzantine Empire, centered in Constantinople, during the 500s. The form crystallized under the creativity of hymnographers such as Romanos the Melodist, who adapted sermonic poetry into a through-composed chant with a prooimion and multiple oikoi sharing the same meter and refrain. Its structure reflects both Greek rhetorical poetics and Near Eastern hymn traditions, delivered within the modal framework of Byzantine chant.

Classical kontakia regularly contained 18–24 oikoi organized as an acrostic, each stanza adhering to the metrical and melodic model set by the prooimion. The refrain (ephymnion) unified the whole, often inviting the choir or congregation to respond. The musical language was syllabic to moderately melismatic, with monophonic melody and later the sustained ison (drone) supporting modal stability. Thematically, kontakia functioned as poetic sermons illuminating feasts, biblical narratives, and theology.

From the Middle Byzantine period onward, the large-scale kontakion yielded liturgical prominence to the developing canon form. In ordinary services, most kontakia were truncated to the prooimion (and sometimes a single oikos), typically appointed after the Sixth Ode of the canon. The most famous exception is the Akathist Hymn, which retains the expansive kontakion architecture and remains widely performed.

Kontakion poetry and performance practice spread with Byzantine Christianity, informing Slavic chant traditions after the Christianization of the Rus. Its poetics, modal ethos, and responsorial design shaped Slavic repertoires (e.g., Znamenny and Kyivan chant), while its theological-homiletic tone influenced broader Orthodox hymnography.

Today, kontakia are performed by trained cantors and specialized Byzantine choirs using Middle Byzantine notation and the Octoechos. Scholarly editions and recordings have revived interest in full-length kontakia, while liturgical practice commonly features the concise prooimion form.