Your digging level

Description

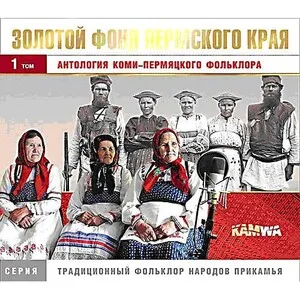

Komi folk music is the traditional music of the Komi people, a Finno‑Permic (Uralic) group living in the far north of European Russia. It is primarily an oral tradition that encompasses solo and group singing, narrative epics, seasonal ritual songs, laments, children’s songs, and lively dance tunes.

Musically, Komi folk practice favors clear melodic lines, modal or pentatonic inflections, and a generally narrow vocal range suited to unaccompanied or lightly accompanied singing. Heterophonic group textures, call‑and‑response refrains, and free‑rhythmic declamation appear in epic or lament genres, while dance repertoires use steady duple or compound meters. Typical folk instruments include end‑blown or fipple flutes, jaw harp (common across Uralic cultures), frame drum or tambourine, fiddle, and—since the 19th century—various accordions (garmon) used for dance.

The repertoire reflects Komi history, livelihood, and beliefs: songs tied to the forest and river landscapes, calendar rites, weddings, and work, alongside narratives shaped by pre‑Christian animistic cosmology and later Orthodox Christian influence.

History

Komi folk music grew from an ancient oral tradition shaped by a northern environment of forests, rivers, hunting, and herding. Before widespread Christianization, songs and vocal rituals reflected animistic beliefs and communal rites, with epic narration, laments, and functional music (work and seasonal songs) forming the core.

From the 1800s onward, scholars and collectors began notating Komi songs, and early sound recordings followed in the early 20th century. This period fixed portions of the repertoire in print and archive, while accordions, fiddles, and other pan‑Russian instruments entered local dance traditions.

In the Soviet era, state and regional folklore initiatives promoted staged performance. Professional and amateur ensembles arranged traditional melodies for choir and mixed instrumental groups, standardizing parts of the style while preserving characteristic modes, refrains, and dance rhythms. Field expeditions also expanded archives with recordings from remote districts.

Since the 1990s, culture centers and community ensembles in the Komi Republic have supported language and song preservation, workshops, and festivals. Contemporary performers often mix archival melodies with modern accompaniment, or re‑emphasize a cappella and small‑ensemble formats, keeping the tradition active in education, ritual, and concert settings.