Kidumbak is a small-ensemble, dance-focused Swahili coastal genre from Zanzibar that grew alongside taarab but emphasizes rhythmic drive and intimate, community performance.

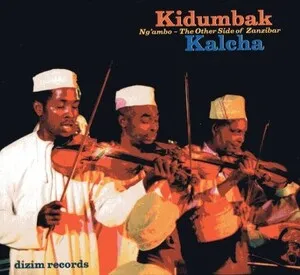

It features two small hand drums (kidumbak), tea‑chest bass (sanduku), shakers or rattles (such as kayamba/mkayamba), clapping, and a lead singer with a responsive chorus. Melodies often reflect Arabic modal flavor (e.g., Hijaz, Bayati) heard in taarab, yet are delivered more briskly and with playful, extroverted vocals.

Unlike the large orchestral sound of taarab, kidumbak thrives at weddings and neighborhood celebrations, where call‑and‑response, witty Swahili poetry, and lively circle dancing take center stage.

Kidumbak emerged in Zanzibar in the early decades of the 20th century as a more intimate, rhythm-forward counterpart to taarab. While taarab’s prestige ensembles drew on Egyptian and broader Arab musical fashions, kidumbak crystallized in small neighborhood groups that foregrounded hand drums, rattles, clapping, and dance. The genre’s name is linked to the kidumbak drums, which anchor its interlocking polyrhythms.

From the 1920s onward, singers associated with taarab also performed kidumbak repertoire at weddings and local festivities. Early recording stars like Siti binti Saad popularized Swahili lyrics, poetic wit, and the performance aesthetics that kidumbak embraced—call-and-response refrains, teasing love songs, and community participation.

After the Zanzibar Revolution and the union with Tanganyika to form Tanzania (1964), kidumbak continued largely as community entertainment, thriving outside formal institutions. Through the cassette era, local groups maintained the style’s social function at family events and neighborhood gatherings, while taarab orchestras dominated stages and state events.

Festivals (such as Sauti za Busara) and new recordings renewed attention to kidumbak’s distinctive groove. Veteran artists (e.g., Bi Kidude) and younger performers (e.g., Siti Muharam, Rajab Suleiman) helped document and revitalize the tradition. In parallel, mainland Tanzanian urban styles absorbed coastal rhythmic sensibilities, with kidumbak’s kinetic drumming ethos echoing in street-party musics like mchiriku and, later, singeli.