Khmer folk music is the village- and community-based musical tradition of Cambodia. It encompasses a wide range of practices: circle-dance songs such as romvong and rom kbach, repartee and satire (ayai), narrative singing with long‑neck lute (chapei dang veng), spirit-invocation repertoires (pleng arak), wedding ensembles (pleng kar), and work songs. These styles share a heterophonic texture in which multiple instruments ornament the same melody, anhemitonic pentatonic tendencies, and a vocal delivery that favors flexible rhythm, melisma, and a slightly nasal timbre.

Typical instruments include bowed fiddles (tro khmer family such as tro sau and tro che), bamboo flute (khloy), the one‑string chest-resonated lute (kse diev), long‑neck fretted lute (chapei dang veng), hammered dulcimer (khim), zither (takhe), various drums (samphor, skor thom), and small cymbals and gongs. While distinct from Cambodia’s courtly pinpeat classical music, Khmer folk idioms borrow modal colors and ornamental practice from it, and in turn shape the social dances, ceremonies, and storytelling that anchor rural life.

Khmer folk music’s roots reach back to the Angkorian era (9th–15th centuries), when village ritual, seasonal festivals, and courtly traditions coexisted. Folk ensembles accompanied Buddhist and animist rites, healing ceremonies (pleng arak), and communal dances, forming a sonic backdrop to agricultural cycles and local storytelling.

Over centuries, Khmer folk styles interacted with neighboring Lao and Thai traditions, sharing circle-dance rhythms and call‑and‑response frameworks. Courtly/classical practice (pinpeat) influenced modal color, ornamentation, and melodic contour, while village musicians maintained simpler, flexible song forms suited to dance and ritual.

From the 1950s to early 1970s, radio and recording spread folk dance songs (romvong, rom kbach) and comedic repartee (ayai) to urban audiences. Wedding ensembles (pleng kar) professionalized, and charismatic singers and chapei bards became widely known, bridging rural styles with modern arrangements.

The Khmer Rouge period (1975–1979) devastated Cambodian musical life; many master performers were lost, instruments destroyed, and transmission lines severed. This rupture profoundly affected both classical and folk repertoires.

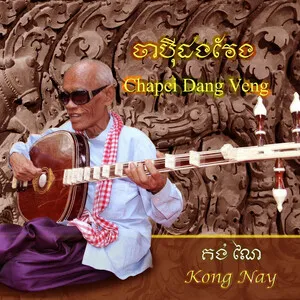

Since the 1980s, cultural programs, the Royal University of Fine Arts, and community masters have rebuilt ensembles and repertoires. Diaspora projects and NGOs such as Cambodian Living Arts helped restore instrument-making and pedagogy. In 2016, Chapei Dang Veng was inscribed by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, symbolizing broader efforts to protect Khmer folk traditions.

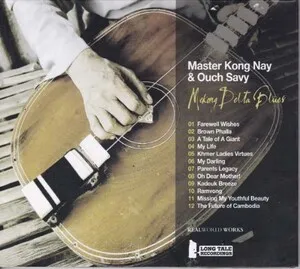

Today, Khmer folk music thrives in weddings, temple festivals, and village gatherings, and engages new audiences via stage showcases and cross-cultural collaborations. Dance songs continue to evolve alongside popular music, while ritual and narrative forms preserve historical memory and local identity.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)