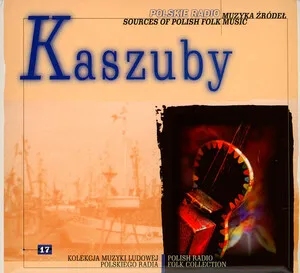

Kashubian folk music is the traditional music of the Kashubians, a West Slavic community native to the Pomeranian (Pomorze/Kaszuby) region of northern Poland. It is sung predominantly in the Kashubian language and preserves regional identity through storytelling, dance, and ritual songs.

The sound is marked by distinctive local instruments such as the burczybas (a friction bass made from a barrel and horsehair rope), the diabelskie skrzypce ("devil’s fiddle"—a percussion idiophone decorated with rattles), the long shepherd or seafaring horn called bazuna, as well as Polish dudy (bagpipes), fiddle, accordion, and frame drums. Rhythms often reflect communal dances (especially lively polkas and stately walking dances) and work songs tied to agriculture and the Baltic coast.

Melodies are typically strophic and diatonic with memorable refrains, call-and-response patterns, and choruses fit for group singing. Lyric themes celebrate coastal life, local customs, love, seasonal rites, and Kashubian history, lending the repertoire both festive and nostalgic colors.

Kashubian folk music developed as an oral tradition over centuries in the Pomeranian countryside and along the Baltic coast. Its earliest layers combined Slavic agrarian song traditions with the seafaring culture of coastal Kashubians. In the 19th century, ethnographers such as Oskar Kolberg began documenting regional repertoires in Pomerania, helping preserve an otherwise orally transmitted tradition.

In the early 20th century, Kashubian cultural activists worked to codify and promote the language and its songs. Composer and folklorist Jan Trepczyk became a key figure, arranging and composing in Kashubian, and shaping a recognizable concert repertoire from local tunes and texts. Despite turmoil during World War II, domestic traditions of singing, dances, and ritual music carried on in communities.

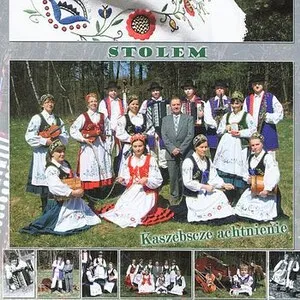

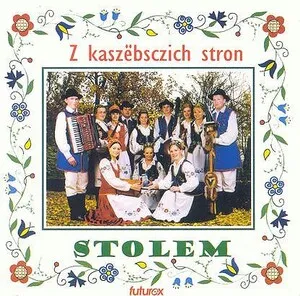

After the war, regional song-and-dance ensembles formed in towns across Kashubia (e.g., Brusy, Kościerzyna, Bytów, Kartuzy), staging choreographed suites that preserved local melodies, costumes, and dances. Open-air museums and regional festivals—such as the long-running gatherings at the Wdzydze Kiszewskie open‑air museum—provided platforms where traditional instruments like the burczybas, bazuna, and diabelskie skrzypce stayed visible.

Following 1989, there was renewed interest in regional identities across Poland. In 2005, Kashubian received legal recognition as a regional language in Poland, further encouraging education and performance in Kashubian. Today, traditional ensembles coexist with bands and singer-songwriters who blend Kashubian folk with folk-rock, pop, and maritime song traditions. Annual cultural events, including the World Kashubian Congress (Światowy Zjazd Kaszubów) and regional festivals, continue to sustain transmission, innovation, and pride in Kashubian musical heritage.