Karelian folk music is the traditional music of the Karelians, a Finnic people whose homeland spans eastern Finland and the Republic of Karelia in Russia. It is best known for runo singing in the Kalevala metre (trochaic tetrameter), a chant-like, incantatory vocal style used to narrate epics, myths, and everyday stories.

Typical sonorities include the kantele (Finnish/Karelian zither) and the jouhikko (bowed lyre), alongside small percussion and occasional fiddle. Melodies are often narrow in range, modal (commonly Dorian and Aeolian), and performed in free or flexible rhythm. Textures lean toward unison or heterophony, with call-and-response between a lead singer and a small chorus. A distinctive subgenre is the Karelian lament (itkuvirsi), marked by free rhythm, sobbing timbre, and improvisatory text formulae.

Owing to its borderland setting, Karelian folk music blends Balto-Finnic runo traditions with influences from Russian folk and Orthodox chant. It has profoundly shaped the Finnish national imagination through the Kalevala and continues to inspire modern folk, folk-rock, and experimental projects.

Karelian musical traditions descend from the wider Balto-Finnic runo-song culture, with deep premodern origins in communal singing, epic recitation, work songs, wedding songs, and ritual laments. Performances were typically solo or leader–chorus, using formulaic poetry, parallelism, and alliteration.

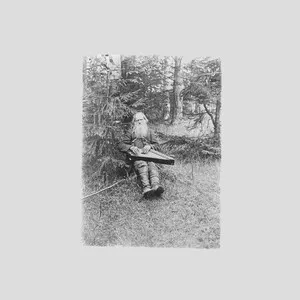

In the 1830s–1840s, collectors such as Elias Lönnrot traveled especially to Viena (White) Karelia to write down runo songs that became the backbone of the Kalevala and Kanteletar. Renowned tradition bearers like Arhippa Perttunen and Ontrei Malinen provided extensive repertoires. This period canonized Karelian styles as emblematic of a broader Finnish identity and spurred interest in the kantele and runo singing across Finland.

With Karelia divided between Finland and Russia, traditions evolved in parallel. In Soviet Karelia, professional folk ensembles (notably the State Ensemble "Kantele") curated staged versions of village repertoires, while in Finland, ethnomusicologists (e.g., A. O. Väisänen) documented field styles and pedagogy. Urbanization and changing social life reduced everyday runo singing, but kantele craftsmanship and regional singing dialects persisted among families and community groups.

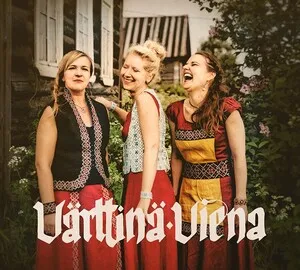

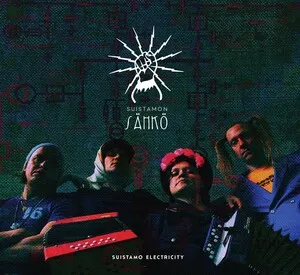

From the 1980s onward, a strong roots revival unfolded. Finnish and Karelian artists revived small‑kantele improvisation, jouhikko playing, and lament traditions, while bands like Värttinä popularized Karelian vocal textures and dance grooves internationally. New projects fuse archival runo texts with electronics or rock instrumentation (e.g., Suistamon Sähkö), and vocal ensembles such as MeNaiset and Suden Aika advanced polyphonic, historically informed performance. Today, Karelian folk music thrives in festivals, conservatories, and community workshops on both sides of the border.