Industrial & noise is an umbrella for abrasive, experimental music that foregrounds distortion, mechanical rhythm, feedback, and non-musical sound sources. It merges the harsh timbral explorations of noise with the confrontational, machine-driven aesthetics of industrial.

Artists typically use found objects, scrap metal, feedback systems, tape manipulation, and heavily processed electronics alongside drum machines and synthesizers. The style ranges from arrhythmic walls of sound to regimented, factory-like beats, often eschewing conventional harmony in favor of texture, density, and psychoacoustic impact.

Thematically, it is frequently transgressive and confrontational—exploring dehumanization, technology, power structures, and catharsis—while performance practice can be theatrical, ritualistic, and intensely physical.

Noise’s conceptual groundwork was laid by early 20th‑century avant‑garde movements (e.g., Futurism) and mid‑century tape and concrete practices (musique concrète, electroacoustic, and studio “tape music”). By the late 1960s and early 1970s, experimental rock (Krautrock), free improvisation, and No Wave normalized feedback, non‑pitched textures, and anti‑virtuosic performance.

The modern industrial idea coalesced in the UK with Throbbing Gristle and Industrial Records—codifying an aesthetic of machine rhythm, transgressive content, and media détournement. Cabaret Voltaire and SPK expanded the palette with tape loops, found sound, and primitive electronics, while the nascent noise underground (soon thriving in Japan) began emphasizing intensity, feedback, and texture over traditional song form.

Industrial splintered across approaches: Einstürzende Neubauten popularized scrap‑metal percussion and architectural sound; Whitehouse defined power electronics’ minimal, high‑intensity feedback and vocal extremity; and a broader post‑industrial network emerged via DIY labels, mail‑art trading, and zines. Parallel scenes in Europe, North America, and Japan fostered distinct idioms—dance‑leaning rhythmic industrial, ritual/ambient strains, and free‑form Japanoise.

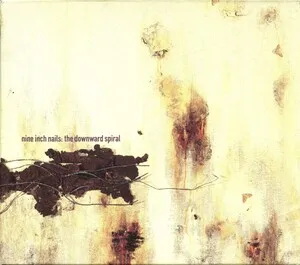

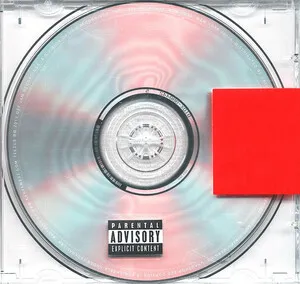

The global cassette/CD underground burgeoned. Noise reached new extremes (e.g., Merzbow’s dense digital saturation; later harsh noise wall’s monolithic stasis). Industrial interfaced with club culture (EBM, industrial metal, and later industrial techno), while labels and micro‑scenes (e.g., Cold Meat Industry, Hospital Productions) pushed dark ambient, death industrial, and power noise. Affordable samplers/DAWs enabled intricate sound design and large‑scale live rigs.

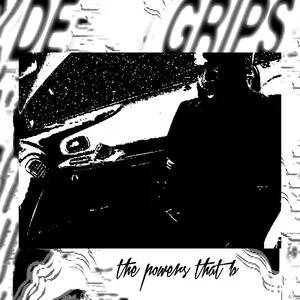

Industrial & noise aesthetics permeate experimental club and sound art: deconstructed club, industrial techno, and noise‑inflected hip hop borrow its distortion, foley‑like design, and confrontational dynamics. Live practice remains central—contact mics on metal, feedback circuits, and immersive amplification—while archival reissues and festivals continue to contextualize the movement’s historical breadth.