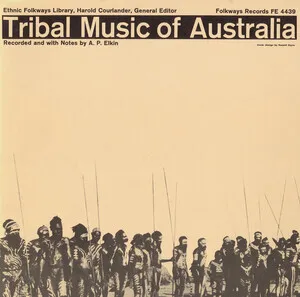

Indigenous Australian traditional music encompasses the song, dance, and instrumental practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that predate colonisation by tens of thousands of years.

At its core are vocal song cycles connected to Country and kinship, often performed with steady percussive accompaniment from clapsticks (bilma) and, in parts of northern Australia, the didjeridu/yidaki drone. Regional styles vary widely: Yolngu manikay (Arnhem Land) feature long, cyclical song series; wangga and kun-borrk (Top End) blend distinctive melodic shapes with clapstick patterns; and Torres Strait Islander traditions centre on harmony singing, conch shell and drum (warup) rhythms, and elaborately choreographed dances.

These musics are living repositories of law, history, and ecology. They are performed in ceremonies for initiation, funerals, healing, and seasonal events, as well as in public community gatherings and welcome ceremonies. Access and performance rights are governed by custodianship, with certain songs and contexts restricted.

Indigenous Australian traditional music is among the world’s oldest continuous musical cultures, with archaeological and oral histories pointing to continuity over tens of millennia. Songlines (Dreaming tracks/Tjukurpa) map routes across Country, encoding ecological knowledge, law, and genealogy in music, dance, and story.

Distinct regional traditions emerged over vast time-scales. In Arnhem Land, the didjeridu (yidaki/mago) developed as a resonant drone instrument accompanying male vocalists and clapsticks. Elsewhere, unaccompanied or clapstick-accompanied singing dominates. Torres Strait Islander music features polyphonic choral textures and percussion (warup drums), reflecting seafaring lifeways and inter-island exchange.

From the late 1700s, displacement, missionisation, and assimilation policies disrupted ceremonial life. Yet many communities maintained, adapted, and revitalised traditions—sometimes integrating new materials (e.g., metal clapsticks, mission hymn tunes in local languages) while preserving core custodial frameworks and ceremonial functions.

Ethnographers and broadcasters recorded performances from the early 20th century onward, creating archives that later supported community-led revivals. Since the late 20th century, cultural centres, ranger programs, and festivals have helped transmit knowledge to younger generations. Traditional musicians collaborate with dance companies and cross-cultural ensembles, presenting song traditions in both ceremonial and public settings while carefully managing cultural permissions.