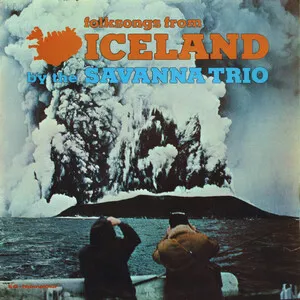

Icelandic folk music is a largely vocal, text-driven tradition rooted in medieval Icelandic verse and saga culture. Its most emblematic form is rímur—long narrative poems delivered in semi-chanting melodies that emphasize internal rhyme, alliteration, and complex stanza forms. Closely related are kvæði (ballads) and tvísöngur (two-part singing in parallel intervals reminiscent of medieval organum).

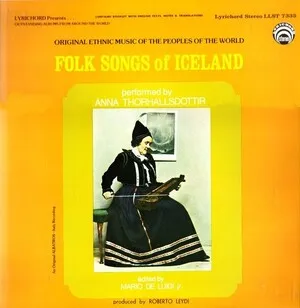

The sound is modal (often Dorian or Mixolydian), frequently free-rhythm or with flexible pulse to follow the text, and typically monophonic or in stark two-part harmony. Traditional instruments include the langspil (an Icelandic bowed zither) and the fiðla (an old fiddle), with later additions like harmonium and accordion in dance and parish settings. Social forms such as vikivaki ring-dances, seafarers’ work songs, and lullabies also belong to the repertoire, reflecting the island’s rural, seafaring, and ecclesiastical life.

Icelandic folk music grows out of the island’s medieval literary and oral culture. From at least the 14th century, rímur flourished as epic, rhymed narrative poetry performed to formulaic tunes. The melodic contour and delivery reflect medieval chant practice and text-first aesthetics, fitting verse meters inherited from Old Norse poetics.

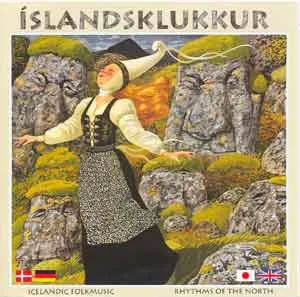

After the Lutheran Reformation, parish singing, hymnody, and domestic devotional music shaped performance practice and repertoire. Tvísöngur (two-part parallel singing) preserved a medieval organum-like sonority well into the modern era. Folk dance and ring-dance forms such as vikivaki spread in the 17th–19th centuries, while oral transmission kept ballads, lullabies, and work songs alive in farmsteads and fishing villages.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, collectors and scholars began notating and preserving the tradition. The clergy-scholar Bjarni Þorsteinsson compiled and published influential collections (Íslenzk þjóðlög, 1906–1909), helping codify melodies and texts that had circulated orally.

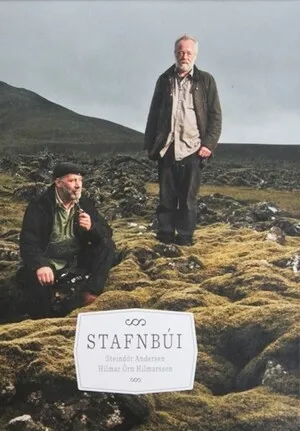

Radio (RÚV) and field recordings captured veteran chanters and singers, including exponents of rímur and tvísöngur. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, a revival brought the langspil back into workshops and stages, and new performers presented rímur both in traditional settings and in collaborations with contemporary composers.

Today, Icelandic folk music survives through societies of chanters (kvæðamenn), dedicated ensembles, festivals, and crossover projects. Artists have presented rímur and kvæði alongside ambient, classical, and popular styles, keeping core traits—modal melody, textual nuance, and austere harmony—central while expanding its audience.