Iberian music is an umbrella term for the intertwined musical traditions of Spain and Portugal, shaped over centuries by Mediterranean, North African, and European currents. It spans sacred chant and courtly song, rural dance traditions, fado and flamenco, art music inspired by folk idioms, and contemporary fusions.

At its core are distinctive rhythmic cycles (such as flamenco compás), modal colors (notably the Phrygian cadence and Hijaz-like inflections), and poetic themes ranging from duende’s raw intensity to fado’s saudade. Guitars (Spanish and Portuguese), clapping (palmas), cajón, castanets, and regional instruments (gaita galega, bandurria, Portuguese guitarra) are central timbral markers.

As a cultural matrix rather than a single style, Iberian music both preserves local identities—Andalusian, Galician, Catalan, Alentejano—and continually reinvents itself in dialogue with classical composition, jazz, rock, and electronic music.

Iberian music crystallized from a unique cultural confluence. Medieval sacred practices included Mozarabic and later Gregorian chant, while Al-Andalus fostered rich exchanges among Muslim, Jewish (Sephardic), and Christian communities. Courtly repertories such as the Cantigas de Santa Maria and later Renaissance polyphony (Morales, Guerrero, Victoria) defined a vocal and liturgical prestige that resonated across Europe.

In the Baroque era, Iberian guitar practices, villancicos, and the birth of zarzuela bridged courtly, popular, and theatrical spaces. Regional dances and song forms spread through pilgrimage routes, marketplaces, and civic festivals, embedding local identity into shared Iberian aesthetics.

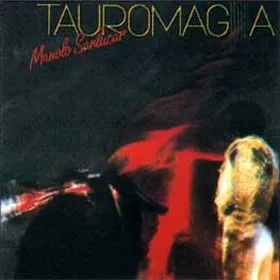

The 1800s saw the rise of musical nationalism. In Spain, flamenco was codified around café cantante culture, consolidating palos (soleá, bulería, seguiriyas) and the expressive ideal of duende. In Portugal, fado emerged in Lisbon’s bairros, with the Portuguese guitarra shaping its ornamented melodic language and themes of saudade. Meanwhile, jota, sardana, muñeira, and pasodoble articulated regional character through dance and parade forms.

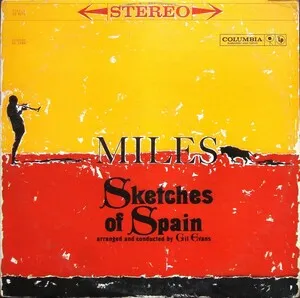

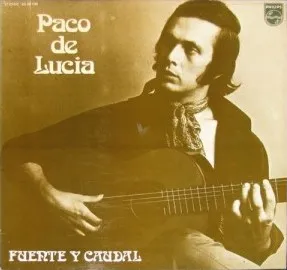

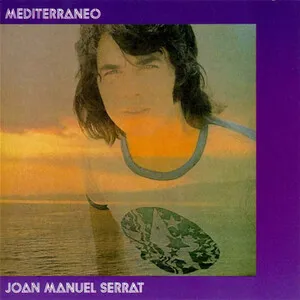

Composers like Albéniz, Granados, and de Falla integrated folk idioms into classical forms, projecting an international “Iberian sound” in art music. Under authoritarian regimes (Franco’s Spain, Portugal’s Estado Novo), music navigated censorship and folk-heritage framing. Postwar urbanization and media spread copla, zarzuela revivals, and regional song movements (nova cançó in Catalonia, nueva canción española). Flamenco innovated through guitar virtuosity and cante evolution, while fado developed modern orchestration and global ambassadors.

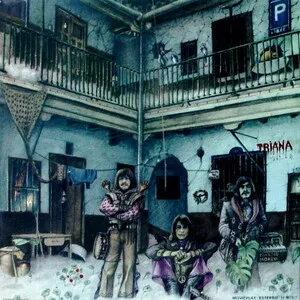

Democratization and globalization amplified cross-pollination: rock andaluz, rumba catalana, nuevo/nueva approaches to flamenco and fado, and broader pop, jazz, and electronic fusions. World-stage recognition (UNESCO listings for flamenco and fado) cemented Iberian music’s heritage status even as artists fuse compás and saudade with hip hop, house, ambient, and experimental production. Today, Iberian music functions as a living matrix connecting tradition and innovation across Spain and Portugal.