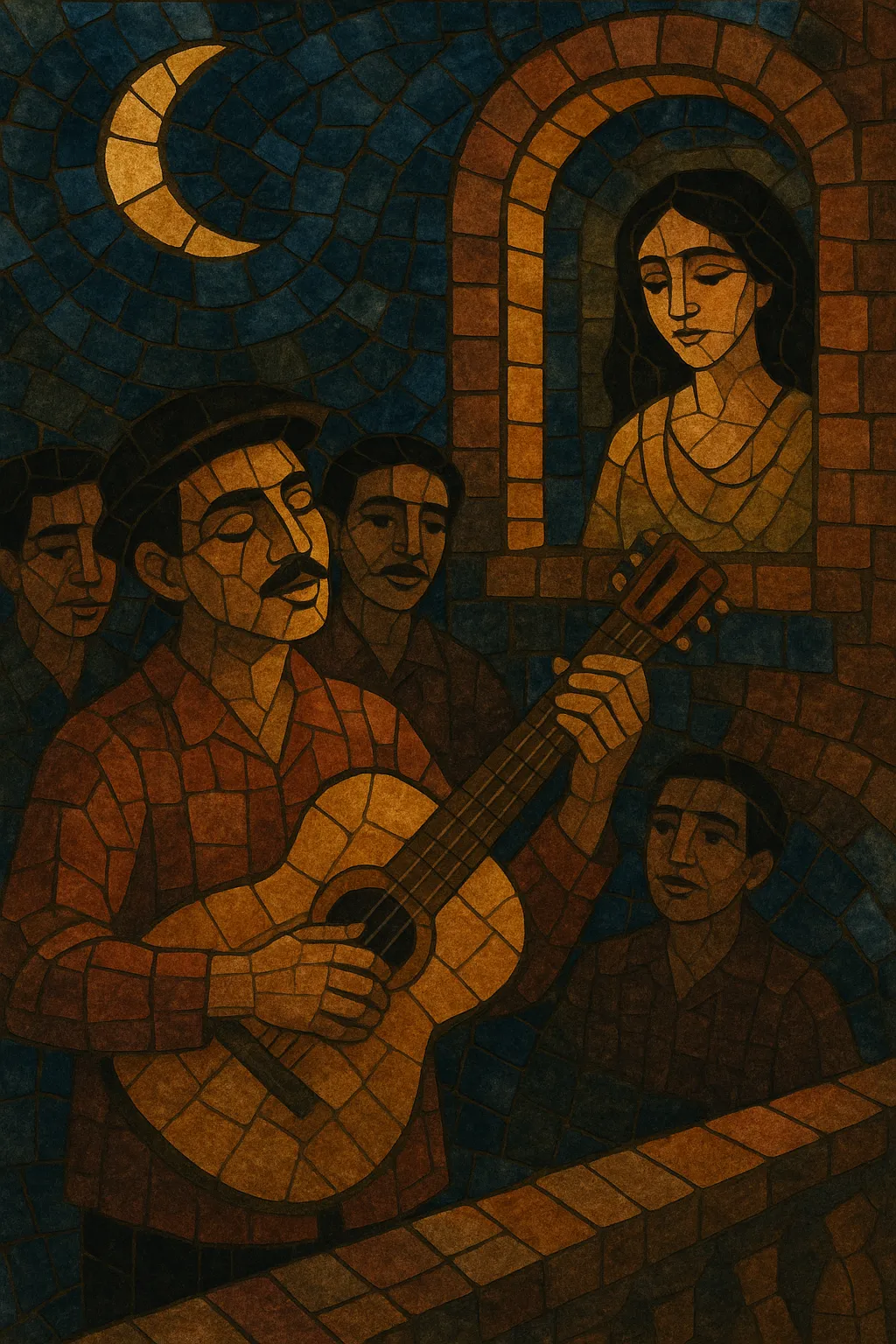

Harana is a Filipino tradition of nocturnal courtship serenades performed outside a woman’s window, typically accompanied by a guitar and a small group of male singers. It took shape during the Spanish colonial period and blends Iberian musical elements with local languages and poetic sensibilities.

Musically, harana favors gentle tempos, lilting Spanish-derived dance rhythms (especially the habanera and occasional waltz), and simple, elegant harmonies that support expressive, melismatic vocal delivery. Lyrics are written in Tagalog (and other Philippine languages), using highly formal, respectful, and flowery language that extols virtue, modesty, and devotion.

While closely related to the more art-song–oriented kundiman, harana is defined by its function as a serenade: a ritualized performance with a call-and-response social script, rather than a concert piece. Its sound world—guitar rasgueado patterns, bass-note–plus–strum accompaniments, and sweet, sentimental melodies—has left a lasting imprint on Philippine love songs and popular ballads.

Harana emerged in the Philippines during the Spanish colonial period as a localized serenade practice. Iberian musical idioms—especially the habanera rhythm and guitar-centered accompaniment—intertwined with Tagalog and other Philippine languages, creating a distinctive courtship ritual. Performances took place at night, outside the beloved’s home, and followed a courteous protocol in which the household acknowledged the singers before the harana formally began.

Unlike concert music, harana’s identity is inseparable from its social function. Songs unfold at a relaxed tempo in 2/4 (habanera) or 3/4 (waltz) time, with clear, lyrical melodies suited to heartfelt declarations. The performance etiquette—respectful greetings, chaperoned listening, and negotiated exchanges—made harana a socially sanctioned form of romantic expression.

In the early to mid-1900s, radio, records, and film helped popularize harana-style songs and singers. Recording artists and composer-lyricists adapted the serenade idiom for urban audiences, preserving its poetic, chivalric character while refining its harmonies and melodic style. During this time, the boundary between harana and kundiman often blurred in the public imagination, even as each kept distinct musical traits.

By the late 20th century, modern courtship patterns and the rise of contemporary pop diminished everyday harana practice. Nevertheless, cultural revivalists, classical guitarists, and heritage projects in the 2000s–2010s documented elder “haranistas,” revived canonical repertoire, and reintroduced harana’s distinctive guitar style and poetics to younger audiences. Its sound, imagery, and etiquette continue to influence Filipino love ballads and nostalgic popular music.