Garifuna folk music is the traditional music of the Garifuna people—an Afro‑Indigenous community whose roots trace to St. Vincent and who settled along the Caribbean coasts of Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, and Nicaragua in the late 18th century. It blends West and Central African polyrhythms with Indigenous Carib and Arawak song practices, and is performed primarily in the Garifuna language.

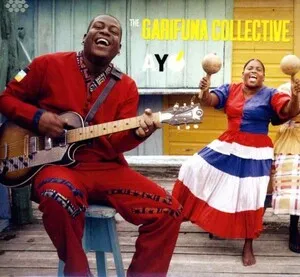

Core styles include the percussion‑driven punta (a fast, social dance music built on interlocking drum patterns and call‑and‑response vocals) and the guitar‑based paranda (intimate, narrative songs influenced by Latin balladry and bolero). Ensembles typically feature two hand drums (primero/tenor and segunda/bass), maracas (sísira), handclaps, and sometimes conch shell horns and turtle shells as idiophones. Vocals often alternate between a lead singer and a responsive chorus, binding music, dance, and community ritual into a single expressive form.

In 1797, the Garifuna (descendants of Africans and Indigenous Carib/Arawak peoples) were exiled from St. Vincent and resettled along the Central American coast, especially in present‑day Honduras. Their music carried forward African polyrhythmic drumming and call‑and‑response singing while preserving Indigenous melodic contours and communal dance functions. By the 1800s, distinct forms such as punta (ceremonial and social dance) and ritual songs tied to ancestor veneration were well established.

Throughout the 20th century, Garifuna communities in Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, and Nicaragua maintained a robust oral tradition. Punta remained central to wakes and communal festivities, while paranda emerged as a reflective, guitar‑accompanied song form, absorbing elements from regional Latin styles (notably bolero). Recording and radio exposure gradually brought Garifuna music from coastal villages to national and regional audiences.

From the 1980s onward, artists and culture bearers began documenting and touring Garifuna music internationally. While a modern electrified offshoot (punta rock) gained commercial traction, tradition bearers and ensembles continued to foreground acoustic, community‑based practice. Landmark projects in the 2000s—such as Andy Palacio & The Garifuna Collective and Umalali—brought global attention to women’s voices and multi‑generational transmission. In 2001, UNESCO proclaimed Garifuna language, dance, and music a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity (later inscribed on the Representative List), underscoring its cultural significance.

Garifuna folk music thrives across Central America and in diaspora hubs (notably in the United States). Community ceremonies, festivals, and educational initiatives support intergenerational teaching of drum‑making, dance, language, and repertoire. Contemporary artists continue to balance preservation with subtle innovations in arrangement, harmony, and production while keeping the core aesthetics—drumming, dance, and communal participation—intact.