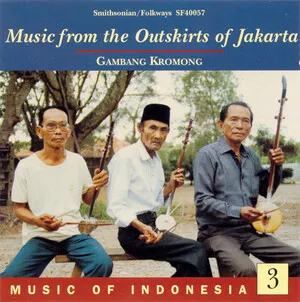

Gambang kromong is a traditional ensemble music of the Betawi people of Jakarta, Indonesia, that fuses Chinese (Tionghoa) musical aesthetics with local Sundanese/Javanese gamelan sensibilities and Malay-poetic song. Its name comes from two of its core instruments: the gambang (a wooden xylophone) and the kromong (a set of small bronze bossed gongs).

Typical ensembles combine Chinese bowed fiddles—tehyan, kongahyan, and sukong—with the gambang, a kromong/bonang-like gong-chime, gongs, frame drums (gendang), metal time-markers (kecrek), and sometimes bamboo flute (suling). Melodically it favors pentatonic modes of Chinese origin adapted to local tunings, and it is performed for social events, weddings, public festivities, and the Betawi social dance known as cokek.

Gambang kromong arose in the 19th century within the multiethnic milieu of Batavia (today’s Jakarta), where Peranakan Chinese communities interacted closely with Betawi (Jakarta-native) society. Musicians adapted Chinese pentatonic song and opera idioms to local instruments and performance practices, building an ensemble centered on the gambang (wooden xylophone) and a small bronze gong-chime called the kromong, alongside Chinese fiddles (tehyan, kongahyan, sukong).

Throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, the style became a hallmark of Betawi celebrations—especially weddings, neighborhood feasts, and social dance events (cokek). The ensemble’s heterophonic textures and lively rhythms made it a natural partner for popular Betawi poetic forms (pantun) and theatrical traditions (such as lenong). Over time, craftsmen standardized the instrument set and local tunings, creating a recognizable Betawi sound while retaining Chinese melodic contours.

In the mid–20th century, some groups incorporated Western instruments (violin, guitar, trumpet) and popular-song formats, giving rise to lighter, more entertainment-focused variants often referred to as “gambang kromong sayur.” Alongside these hybrids, classical (klasik) ensembles continued to maintain the traditional repertoire. Since the late 20th century, cultural organizations and Betawi community institutions in Jakarta—especially at Setu Babakan cultural village—have supported training, instrument making, and performances to ensure the genre’s continuity amid rapid urban change.