The Fort Thunder scene refers to a mid/late‑1990s DIY art‑and‑noise community centered around the Fort Thunder warehouse in Providence, Rhode Island. It fused blistering noise rock, no wave abrasion, hardcore punk energy, and comic‑book/screen‑print visual culture into immersive floor‑level performances.

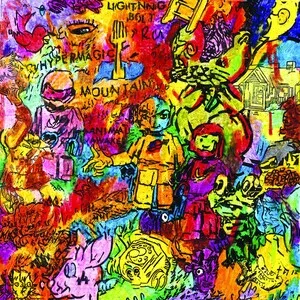

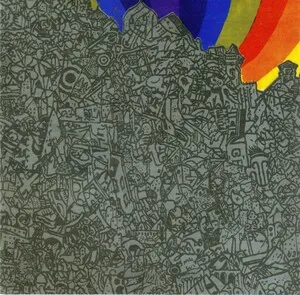

Musically, it favored maximal volume, distorted bass guitar (often the only stringed instrument), hyperactive polyrhythmic drumming, clattering electronics, contact‑miked objects, and improvised/through‑composed structures that prized texture and momentum over conventional harmony. Aesthetically, shows were carnivalesque: masks and costumes, hand‑silkscreened posters, projections, and sculptural set pieces turned concerts into total environments.

Although place‑specific, the Fort Thunder scene became a shorthand for a raw, ecstatic, visual‑arts‑driven strain of American noise/experimental rock that spread via touring, zines, tapes, and labels like Load Records.

Fort Thunder began in 1995 when artists/musicians (notably Brian Chippendale and Mat Brinkman) turned a former textile warehouse in the Olneyville neighborhood of Providence into a live/work/performance space. The proximity to RISD and a thriving poster/zine culture fed a DIY ecosystem where bands, comics makers, and screen‑printers cross‑pollinated. Early shows established the signature approach: floor‑level sets, costumed performers, towering volume, and hand‑made visuals saturating the room.

By the late 1990s the warehouse was a magnet for touring experimental acts, while homegrown groups like Lightning Bolt, Arab on Radar, Mindflayer, Landed, Thee Hydrogen Terrors, and the art collective/band Forcefield defined the sound and look. Load Records documented and exported the scene’s intensity on tape and vinyl, helping Providence become synonymous with a new wave of American noise rock. Word spread through xeroxed zines, posters, and national DIY touring networks.

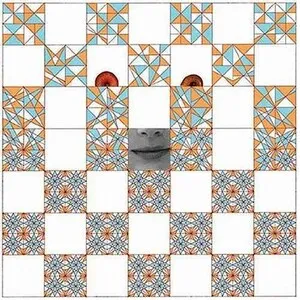

The Fort Thunder building was slated for redevelopment (Eagle Square), and the space was ultimately shut and demolished by the early 2000s. Even as the physical site vanished, its artists dispersed, forming new projects (e.g., Black Pus, Chinese Stars) and carrying the aesthetic to galleries and festivals—Forcefield represented the Providence sensibility at the 2002 Whitney Biennial, highlighting the scene’s art/music hybridity.

The Fort Thunder approach—noise‑driven performance as total artwork, community‑minded curation, and print‑rich visual identity—influenced DIY venues across the U.S., nourished the 2000s noise underground, and fed into broader movements like New Weird America and "brutal prog." Its emphasis on ecstatic physicality, handmade ephemera, and floor‑show intimacy remains a template for experimental communities worldwide.