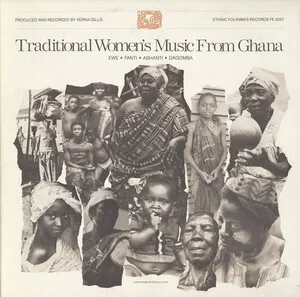

Ewe music is the traditional musical culture of the Eʋe (Ewe) people of southeastern Ghana and southern Togo, known for its intricate polyrhythms, responsorial singing, and integrated dance.

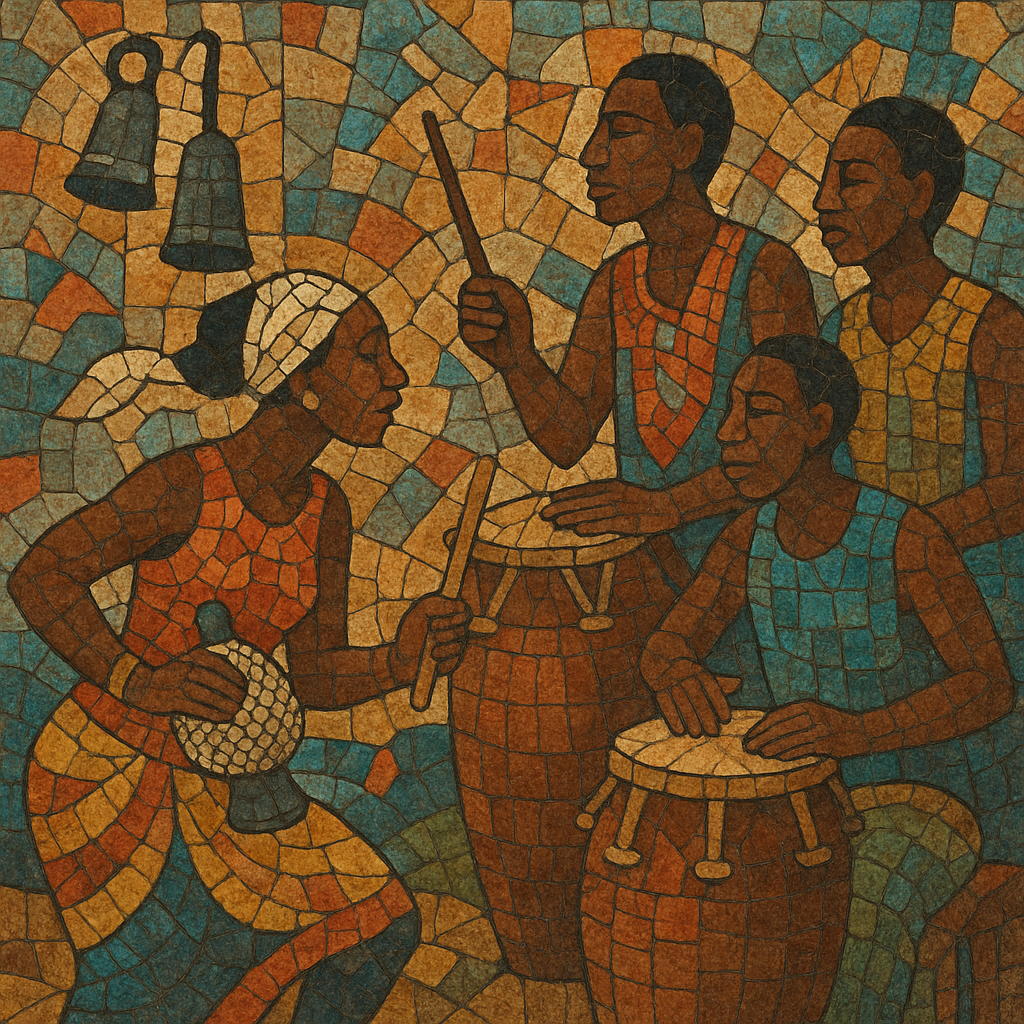

At its core is a time-keeping bell pattern (gankogui) and a beaded gourd rattle (axatse), over which a family of drums—most prominently the atsimevu (lead drum), sogo, kidi, and kagan—interlock in cross-rhythms. A master drummer shapes the form, signaling entrances, breaks, and dance cues with improvisatory phrases.

Songs are typically in the Eʋegbe language and use call-and-response textures, with choruses supporting a lead singer. Repertoires such as Agbadza (a social dance with roots in war music), Atsiagbekor (a virtuosic former war dance), Gahu (a lively social dance), Kinka, and Gota are performed at festivals, funerals, initiations, and communal celebrations.

The music is inseparable from dance and social meaning: rhythm, song, and movement form a single art that encodes history, morality, and community identity.

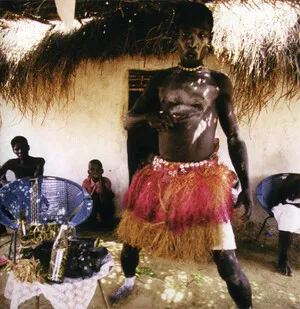

Ewe musical practice crystalized in the precolonial era as part of civic, military, and ritual life in Ewe-speaking communities that migrated and settled in present-day southeastern Ghana and southern Togo. Ensembles organized around a time-line bell, rattle, and families of drums articulated social roles: war associations, age-grade societies, and religious fraternities each maintained distinct repertories.

Under colonial rule, older martial repertories (e.g., Atrikpui) were recontextualized into public social dances. Agbadza, today a hallmark of Ewe identity, emerged as a widely shared recreational form derived from earlier war drumming and song. Guilds of master drummers codified pedagogy, stick techniques, and ensemble etiquette, preserving repertories while allowing local variants to flourish.

Following Ghana’s independence (1957), national and university ensembles incorporated Ewe repertories, elevating them on concert stages. Scholars and artists such as A. M. Jones, J. H. Kwabena Nketia, and later David Locke documented Ewe rhythm and form. Ewe master drummers—including members of the Ladzekpo family, Godwin Agbeli, and Gideon Alorwoyie—taught internationally, shaping the understanding of African polyrhythm in conservatories and dance departments.

Today, village-based troupes, cultural institutes (e.g., Dagbe Cultural Institute), and university ensembles maintain lineages while adapting presentation for schools, festivals, and recordings. Core structures—bell timelines, interlocking drum ostinati, master-drummer leadership, and call-and-response song—remain stable, even as staging, tempo, and costume evolve. Ewe concepts of rhythm and ensemble coordination have profoundly influenced global percussion pedagogy and contemporary composition.