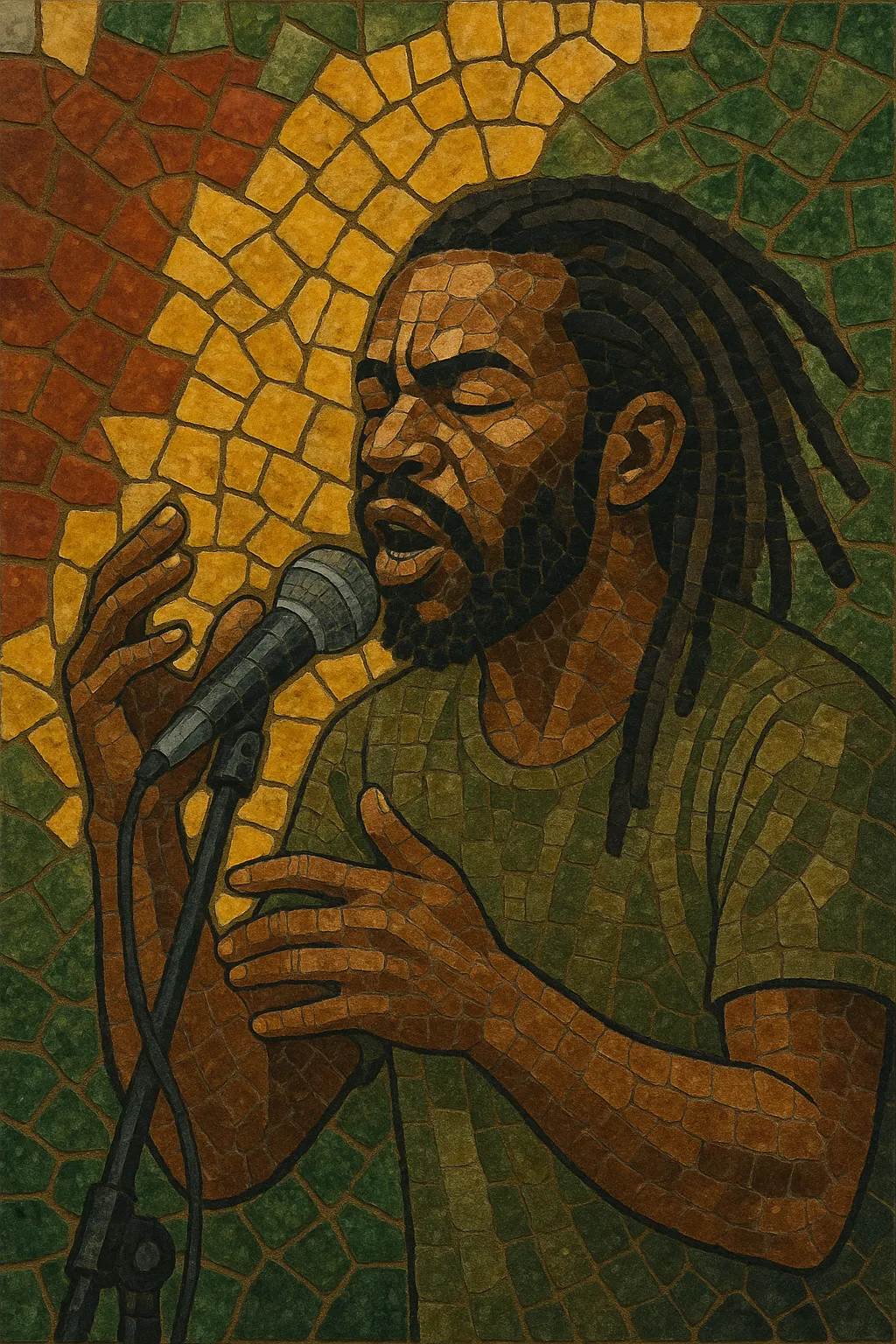

Dub poetry is a form of performance poetry that merges spoken-word delivery with the bass-heavy, spacious rhythms of reggae and dub.

Unlike Jamaican toasting (the DJ "talk-over" tradition), dub poets typically recite crafted, page-ready poems with deliberate meter, imagery, and rhetorical structure, performing them over live bands or pre-recorded "version" tracks sculpted with echo, delay, and reverb.

The style is closely tied to Rastafarian consciousness and social commentary, addressing themes such as anti-racism, diaspora identity, working-class struggle, and state violence. Vocals are often delivered in Jamaican patois (or Caribbean English), with strong rhythmic phrasing that locks into one‑drop and steppers grooves while the mix engineer uses dub techniques to frame the voice in space.

Dub poetry emerged in Kingston’s vibrant reggae and sound-system milieu in the mid-to-late 1970s. Building on the studio innovations of dub and the social ethos of roots reggae, poets adapted the mic-centered immediacy of yard performances into crafted, literary recitation. Early foundational figures include Oku Onuora (often called the "father of Jamaican dub poetry"), whose prison writings and performances joined political urgency to roots riddims.

The genre rapidly took hold in the UK’s Caribbean diaspora, where immigrant experiences and anti-racist struggles gave it sharp focus. Linton Kwesi Johnson’s recordings with producer/bassist Dennis Bovell—beginning with Poet and the Roots’ "Dread Beat an’ Blood" (1978) and followed by "Forces of Victory" (1979) and "Bass Culture" (1980)—cemented the template: page-based poetry performed with a tight dub-reggae band and studio-as-instrument production. Michael “Mikey” Smith’s "Mi Cyaan Believe It" (1982), Mutabaruka’s "Check It!" (1983), and Jean “Binta” Breeze’s groundbreaking work (as the first widely recognized female dub poet) broadened both voice and perspective.

As reggae’s global influence spread, dub poetry took root in Canada (e.g., Lillian Allen and Afua Cooper), across the UK (Benjamin Zephaniah, Levi Tafari), and in performance circuits linking literature festivals, community centers, and sound-system stages. The form’s marriage of militant message and spacious, bass-forward production made it a touchstone for politically engaged spoken word.

Dub poetry’s imprint can be heard in contemporary spoken word and slam scenes, in politically conscious hip hop, and in cross-genre collaborations that keep dub’s studio aesthetics alive. While the classic one‑drop groove and live band remain central, modern practitioners also employ digital riddims, live dubbing, and multimedia performance to carry forward its activist poetics.