Your digging level

Description

Doina is a free-rhythm, highly ornamented, improvisatory song form from Romania (also found in Moldova and neighboring regions). Traditionally performed as an unmetered vocal lament or a rhapsodic instrumental solo, it foregrounds expressive rubato, melismas, and microtimbral nuance.

Its melodies draw on modal pitch collections—often Dorian, Aeolian (natural minor), and, in many klezmer-influenced settings, the Ahava Rabbah/Hijaz (Phrygian dominant) mode with characteristic augmented seconds. Phrases expand and contract with breath and emotion rather than a fixed pulse, typically ending with a sighing descent to the tonic.

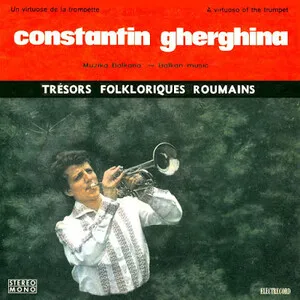

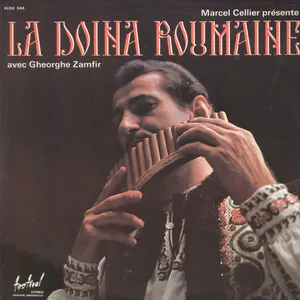

Common timbres include solo voice, nai (pan flute), fluier (shepherd’s flute), violin, and, in lăutar ensembles, cobza and cimbalom; in klezmer contexts, clarinet or violin carries the doina. The piece can stand alone as an introspective lament or serve as a prelude to a lively dance tune (e.g., hora, sârba, or freylekhs).

History

Doina likely predates written documentation, emerging from rural shepherd and lăutar (Romani professional musician) traditions as a vehicle for personal expression—longing, separation, love-sorrow, and contemplation of nature. Its unmetered, breath-shaped phrasing and ornamented modal melodies align it with broader Eastern and Southeastern European lament and improvisation practices.

Ethnographers and collectors in the 19th century began describing the doina as a distinctive Romanian genre (closely related to the hora lungă “long song”). Lăutar ensembles cultivated instrumental doinas on violin, nai, and cimbalom, bringing the form from the countryside into towns, salons, and later early recordings.

Jewish musicians in Romanian lands adopted and transformed the doina into a hallmark of klezmer performance: a rhapsodic, freely timed solo (often on clarinet or violin) that precedes or contrasts with dance pieces. In that setting, modal vocabularies such as Ahava Rabbah/Hijaz and cantorially inspired inflections became prominent, creating a distinct but traceable branch of the doina lineage.

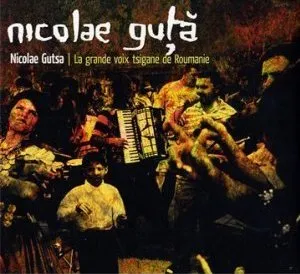

During the interwar and socialist eras, the doina moved onto radio and stage via celebrated singers and lăutari, while state ensembles curated it within staged folklore programs. Iconic interpreters showcased both vocal and instrumental styles, keeping the tradition visible even as urbanization shifted musical life.

Today, doina remains a living practice among traditional Romanian and Moldovan musicians, Romani lăutari, and klezmer performers worldwide. Conservatories, archives, and folk revivals preserve historical variants, while contemporary artists adapt the form in world, jazz, and fusion contexts—retaining its core traits: free rhythm, modal inflection, and intense, personal expressivity.

How to make a track in this genre

Top albums