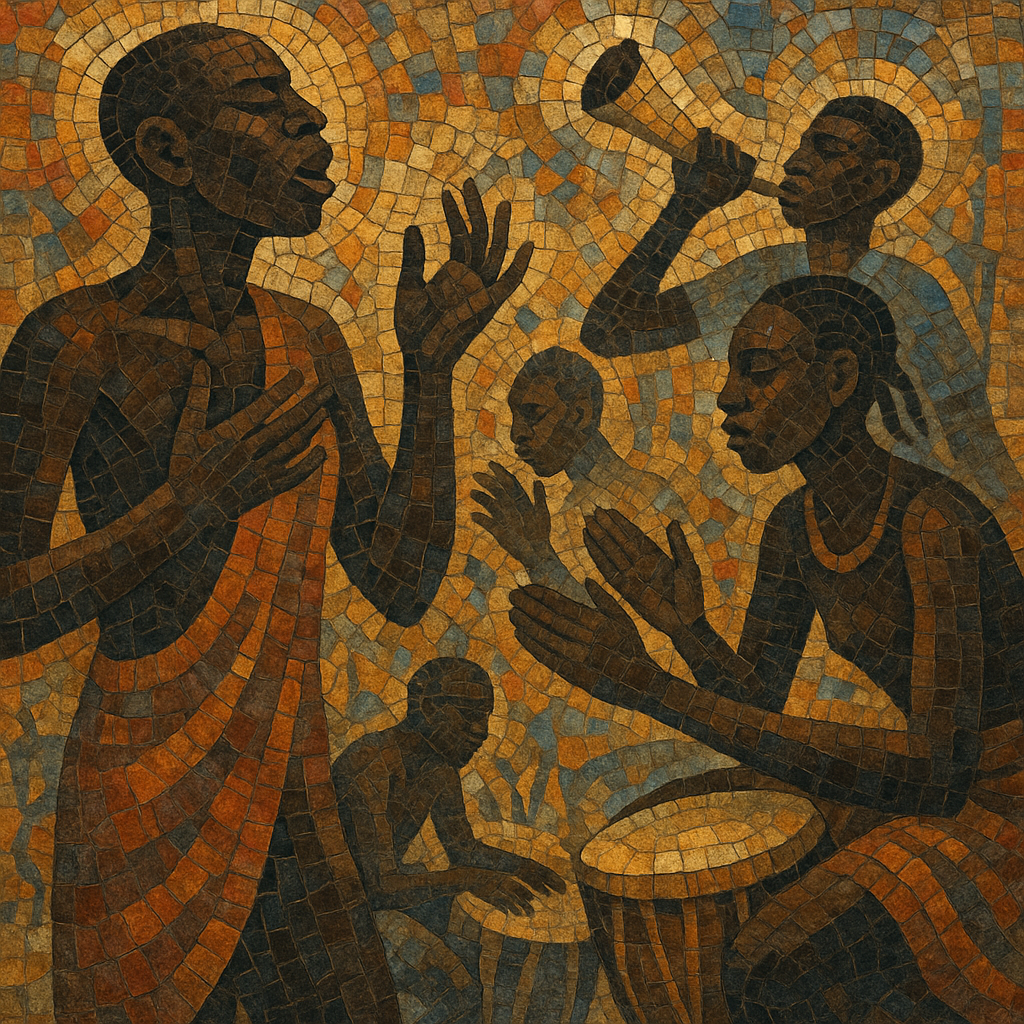

Dinka music is the traditional vocal- and rhythm-centered music of the Dinka (Jieng) people of South Sudan. It is predominantly collective and participatory, built around a lead singer who cues a chorus in call-and-response, supported by handclaps, foot-stomps, ululations, and simple percussion.

Melodies often sit in narrow ranges and unfold through repetition and subtle variation, producing a strong, trance-like groove. Texts celebrate cattle, clan identities, personal praise, historic events, migrations, and social virtues, with distinctive poetic imagery tied to cattle-camp life.

Instrumental accompaniment is sparse but can include large skin drums, calabash and gourd percussion, ankle rattles, cowhorns, and whistles. Rhythms emphasize interlocking patterns and off-beat accents typical of Nilotic and East African performance, creating an energetic, danceable feel.

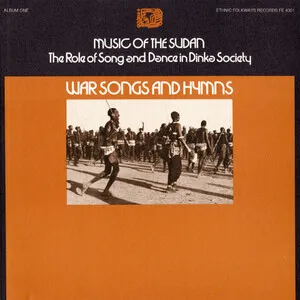

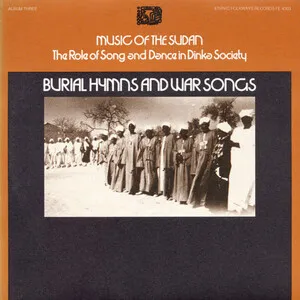

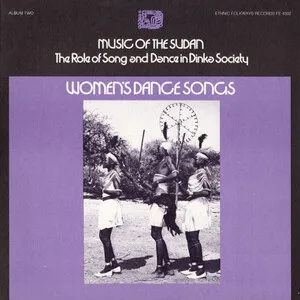

Dinka music predates written history and is deeply embedded in the social fabric of the Dinka (Jieng) people. Songs are integral to cattle-camp life, communal celebrations, initiation rites, weddings, wrestling matches, and funerary observances. The tradition prioritizes communal participation over virtuoso display, with a designated song leader guiding the group.

From the late 19th to 20th centuries, colonial administration and missionary activity introduced church hymnody and choral singing into Dinka regions. While these did not replace traditional repertoire, they created parallel practices and occasional stylistic exchange (for example, call-and-response hymn singing shaped by local rhythmic sensibilities and, conversely, traditional songs adopting multipart textures).

Civil wars and displacement in the late 20th and early 21st centuries dispersed Dinka communities to towns and diaspora hubs (Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, and beyond). Cattle-camp song practices adapted to urban spaces and community centers, with cultural troupes formalizing performances for festivals and heritage events. Oral transmission remained central, with elders and song leaders teaching younger singers.

In recent decades, NGOs, radio archives, and ethnographic recordings have helped document Dinka songs, while community ensembles perform at national days and diaspora gatherings. Although modern popular styles in South Sudan continue to grow, traditional Dinka music endures as a marker of identity, with its poetic cattle imagery and participatory rhythms continuing to define the genre.