Your digging level

Description

Digital dancehall is the computer‑driven evolution of Jamaican dancehall that emerged in the mid‑1980s, when riddims began to be built almost entirely with drum machines and synthesizers instead of live bands.

It is defined by stripped‑down, syncopated drum patterns, heavy sub‑bass, bright digital stabs and horn hits, and a minimalist, loop‑centered approach to harmony. Vocals range from gruff, rapid‑fire toasting to melodic singjay styles delivered in Jamaican patois, often addressing party culture, street life, slackness, and social commentary.

Typical tempos sit around 85–100 BPM, leaving space for the deejay to ride the riddim with rhythmic precision. Production leans on crisp, quantized drums (influenced by early digital gear) and creative use of delay and reverb inherited from dub, while the focus remains on the riddim as a reusable backbone for multiple vocal versions.

History

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Jamaican dancehall evolved out of roots reggae and sound‑system culture, with live or semi‑live "rub‑a‑dub" bands backing deejays. Dub’s studio experimentation and sound‑system competitiveness primed producers to adopt new technology as soon as it became accessible and rugged enough for dancefloor use.

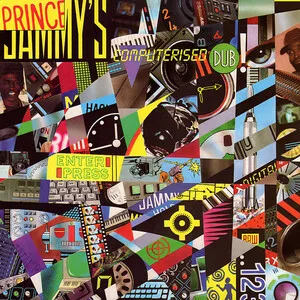

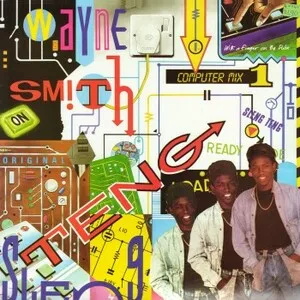

The watershed moment arrived in 1985 with Wayne Smith’s "Under Mi Sleng Teng," produced by (Prince) King Jammy. Built on a preset from the Casio MT‑40 keyboard and augmented with drum machine programming, "Sleng Teng" showed that a fully computerized riddim could mash up dances, triggering a rapid shift away from live backing towards drum machines, synth basses, and digital stabs. Within months, dozens of versions appeared, and the "computerised" sound swept Jamaica.

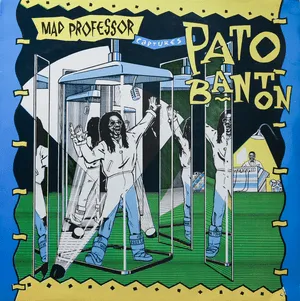

Producers like King Jammy, Steely & Clevie, and Gussie Clarke standardized the aesthetic: punchy, quantized drums; booming digital bass; sparse, catchy motifs; and reusable riddims voiced by multiple artists. Deejays and singjays such as Shabba Ranks, Super Cat, Ninjaman, Admiral Bailey, Johnny Osbourne, and Cutty Ranks rode these riddims to international visibility. The concise 7‑inch single remained the core format, while sound systems pushed exclusives (dubplates) to win clashes.

Digital dancehall reshaped global pop and club music. Its riddim logic and vocal cadence informed ragga hip‑hop and the UK’s jungle and ragga jungle scenes, while the "dembow" rhythmic cell (crystallized on Shabba Ranks’ "Dem Bow") became a cornerstone of reggaeton. Elements of its bass weight, patter, and minimalism echo through grime, moombahton, and modern global club hybrids.