Cuban charanga is a Cuban dance-music style and ensemble format distinguished by its light, elegant sound built around wooden or modern flute, multiple violins, piano, double bass, güiro, and timbales (paila criolla), with little to no brass.

It originally accompanied danzón in Havana ballrooms, later becoming the vehicle for danzón‑mambo, cha‑cha‑chá, and pachanga. The music emphasizes graceful melodies, interlocking rhythmic cells such as the cinquillo and tresillo, and a refined, chamber‑like timbre that invites both social dancing and close listening.

Charanga grew from the Havana ballroom tradition surrounding danzón, which itself descended from the Cuban contradanza and habanera. Around the 1900s–1910s, ensembles called charanga francesa replaced the earlier brass-heavy orquesta típica with a more intimate combination of flute, violins, piano, bass, güiro, and timbales. Antonio María Romeu helped define the idiom’s lyrical, salon-like character.

In the 1930s–40s, Antonio Arcaño y sus Maravillas—with bassist-composer Israel “Cachao” López and Orestes López—modernized charanga repertoire through danzón-mambo, adding more syncopation, call-and-response montunos, and instrumental solos while maintaining the elegant charanga instrumentation. This experimentation laid key foundations for the later mambo boom.

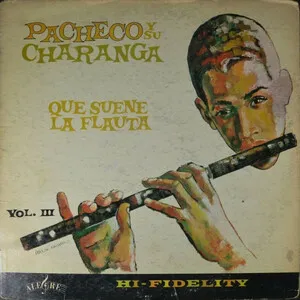

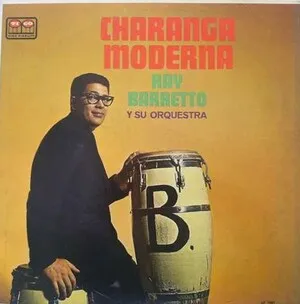

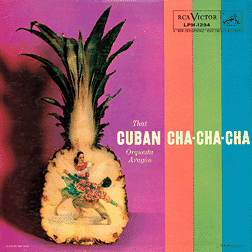

In the early 1950s Enrique Jorrín, working within a charanga setting (Orquesta América), introduced cha‑cha‑chá, a simplified, catchy rhythmic pattern that spread globally. Charanga orchestras such as Orquesta Aragón, Fajardo y sus Estrellas, and Orquesta Sensación popularized both danzón and cha‑cha‑chá. In New York at the turn of the 1960s, Johnny Pacheco’s flauta-and-violins charanga ignited the pachanga dance craze, bringing the charanga sound into the U.S. Latin scene.

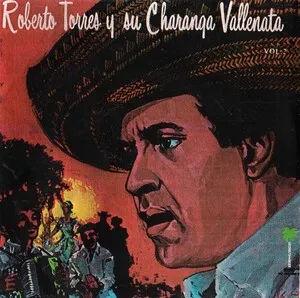

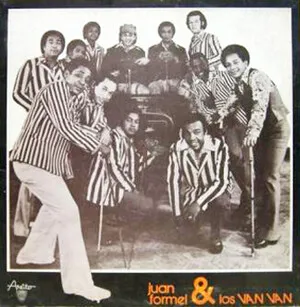

During the salsa era, charanga’s timbre and arranging approach influenced charanga‑salsa projects (e.g., Charanga 76) and informed the flute-and-strings palette heard alongside harder son and salsa formats. While brass-led ensembles dominated salsa, charanga retained a dedicated following in Cuba and abroad. Orquesta Aragón continued as a cultural institution, and charanga textures remain central to traditional danzón and cha‑cha‑chá performance, as well as a reference point for modern Latin jazz and dance music.

Cuban charanga endures as both a performance practice (the charanga ensemble) and a recognizable aesthetic—elegant, melodically rich, and deeply danceable. Its role in birthing cha‑cha‑chá, energizing pachanga, and seeding mambo’s rhythmic ideas secures its place at the core of Cuban and pan‑Latin dance-music history.

Use the classic charanga lineup: one lead flute (historically wooden simple‑system; today often Boehm C flute), 2–4 violins (in unison or simple harmonized lines), piano, double bass, güiro, and timbales. A single conga can be added in later styles, but brass is typically absent.

Base the groove on Cuban danzón cells: tresillo and cinquillo distributed among güiro, timbales, piano, and bass. Keep tempos moderate for danzón (around 90–110 BPM) and brighter for cha‑cha‑chá or pachanga (110–130 BPM). Timbales mark time with light cascara patterns; güiro provides a constant, elegant scrape that locks in the dance feel.

Favor diatonic, song‑like progressions with occasional secondary dominants and chromatic approach chords. Traditional danzón uses sectional forms with a paseo (intro) followed by contrasting themes, while cha‑cha‑chá and pachanga often include a montuno section (call‑and‑response coro and lead, plus flute/violin solos). Keep cadences clear and phrasing symmetrical to support dancers.

Write singable, lyrical melodies for flute and violins. Use violins in tight unisons or in thirds/sixths for sweetness; reserve the flute for ornaments, turns, and virtuosic breaks during montunos. Piano should combine sparse, syncopated guajeos with occasional classical-style arpeggiation in danzón passages. Bass plays a steady, danceable tumbao; avoid overly busy lines that obscure the elegant flow.

Prioritize acoustic clarity and balance so strings and flute sit on top of the rhythm section. Keep percussion crisp and not overpowering. In live settings, emphasize dynamics—lighter in the paseo, fuller in the montuno—to guide the dance floor. If fusing with modern styles, preserve the charanga timbre (flute + violins) as the signature voice.