Cretan folk music is the traditional music of the island of Crete, characterized by the singing of improvised poetic couplets (mantinades), modal melodies, and a powerful dance culture. Its most iconic sound is the dialogue between the bowed Cretan lyra and the percussive laouto (Cretan lute), often joined by violin, the local bagpipe (askomandoura), and occasionally boulgari, mandolin, or frame drum.

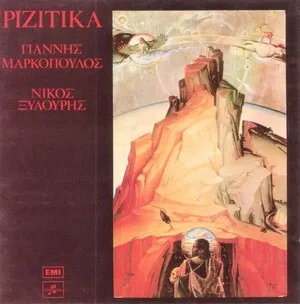

The repertoire is built around dance forms such as syrtos (and its local variants), pentozali, sousta, siganos, and maleviziotikos, alongside non-dance epic or lyrical songs like the mountain-born rizitika. Stylistically it blends Byzantine chant’s modal ethos with Eastern Mediterranean makam practice and Greek island folk idioms, producing melodies rich in ornamentation, drones, and rhythmic lift.

In social life it is inseparable from feasts (gléntia), weddings, and village festivals, where singers trade mantinades in call-and-response while dancers circle in communal lines. Modern artists maintain the core while expanding its timbre and harmony through creative, yet respectful, innovation.

Cretan folk music descends from a long continuity of Aegean island traditions, Byzantine sacred and paraliturgical song, and Ottoman-era modal practice. Village dance forms (syrtos, sousta, pentozali) and heroic or contemplative songs (rizitika) were transmitted orally. The lyra—today’s emblematic bowed instrument—coexisted with violin and laouto and, in rural settings, with the askomandoura.

The emergence of recording technology and urban music hubs helped codify a recognizably “Cretan” sound. Local players standardized the lyra–laouto ensemble and crystallized regional variants of dances. Mantinades—15-syllable rhymed couplets—became the signature vehicle for improvisation, humor, romance, and social commentary.

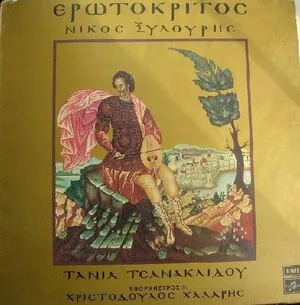

Virtuosi such as Kostas Mountakis and Thanasis Skordalos defined modern technique and repertoire. Nikos Xylouris brought Cretan vocalism and ethos to national prominence, while Stelios Foustalieris bridged traditions through lute and boulgari. The period balanced village authenticity with growing concert stages and radio.

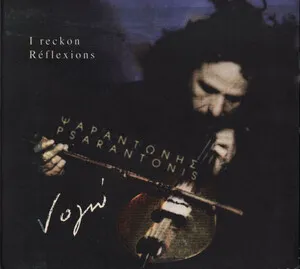

Artists including Psarantonis (Antonis Xylouris), Vasilis Skoulas, Michalis Tzouganakis, and ensembles like Hainides expanded the palette—exploring modal improvisation (taximia), new tunings, and cross-cultural timbres (notably via Ross Daly’s lab of modal traditions). Contemporary Cretan music thrives in festivals and local feasts, retaining communal dance functions while inspiring world-fusion, folk-rock, and art-song reinterpretations.

Cretan folk music remains a living social practice: dancers, singers, and instrumentalists co-create the event. It functions as both identity marker and artistic discipline, with mantinades and dance cycles serving as vehicles for memory, storytelling, and communal celebration.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)