Coptic music is the liturgical chant tradition of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, preserved primarily through oral transmission and performed in the Coptic (Bohairic) language, with Arabic and occasional Greek refrains. It is characterized by long, ornate melismas, responsorial or antiphonal textures between a lead cantor (muallem) and deacons/choir, and a modal, non-tempered intonation closely aligned with regional maqām practice.

Instrumentation is minimal: small hand cymbals (senj) and triangle reinforce pulse in festive and processional hymns, while much of the repertory is either rhythmically free or features flexible meters. The repertoire is organized by liturgical season (e.g., Kiahk, Great Lent, Holy Week, Pentecost) and by traditional hymn families and modes (e.g., Adam and Batos forms), each associated with specific services and theological themes.

Although it shares general features with other Eastern Christian chant families, Coptic music retains distinctive Egyptian contours—often described as deeply melismatic, rhetorically declaimed, and intensely devotional—linking early Christian Egypt to later Arabic musical aesthetics.

Coptic music emerged in the Christian communities of Roman and Byzantine Egypt, crystallizing by roughly the 300s–500s CE. As the liturgy developed in Alexandria, older Egyptian melodic habits blended with Hellenistic and early Christian chant practices. The primary vehicle was the Coptic language (eventually the Bohairic dialect), and the tradition was transmitted orally by master cantors (muallemeen).

Following the Arab conquest (7th century), the Church continued its chant in a predominantly Arabic-speaking environment. Over centuries, melodic contours and intonation increasingly reflected the surrounding maqām-based aesthetics, while maintaining a clearly ecclesial identity and minimal instrumentation (voice, hand cymbals, triangle). Hymns were organized by feasts, fasts, and ritual actions, with specialized melodies for seasons such as Kiahk and Holy Week.

The tradition remained largely unwritten until the 20th century. Musicologist Ragheb Moftah spearheaded a monumental preservation project, recording leading cantors—especially Muallem Mikhail Girgis El-Batanouny—and commissioning transcriptions from Ernest Newlandsmith (1928–1936) and later scholars such as Margit Toth. These efforts, along with the Higher Institute of Coptic Studies in Cairo, created archives and pedagogical resources that stabilized the oral tradition.

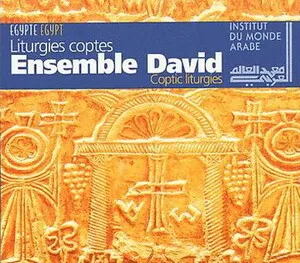

Since the late 20th century, choirs and ensembles (e.g., The David Ensemble) have presented Coptic hymns in concert settings and recordings, sometimes adding choral drones or discreet harmonizations for educational contexts. In Egypt and the global Coptic diaspora, liturgical performance remains primarily unaccompanied and cantor-led, while curated archives and digital platforms have broadened access and standardized variants across communities.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)