Chinese music is a broad umbrella covering millennia of ritual, courtly, theatrical, and folk traditions bound by distinct tonal systems, timbres, and aesthetics. At its core, it emphasizes pentatonic and heptatonic modal thinking (gong, shang, jiao, zhi, yu), flexible rhythm, and expressive ornamentation such as slides, bends, turns, and vibrato.

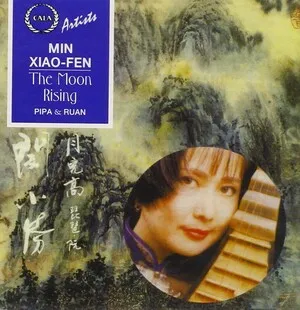

Typical textures are heterophonic: multiple instruments render the same melody with individualized embellishment rather than Western-style chordal harmony. Signature timbres come from silk-and-bamboo instruments like the guqin and guzheng (zithers), pipa and ruan (lutes), erhu (bowed fiddle), dizi and xiao (flutes), sheng (mouth organ), and suona (double-reed), often supported by gongs, cymbals, and drums in percussion-driven ensembles.

The repertoire spans refined court and literati genres, regional folk songs, and powerful theatrical traditions (e.g., Beijing opera and Kunqu), as well as modern large Chinese orchestras and contemporary fusions. Across its diversity, the music foregrounds melodic rhetoric, programmatic imagery, and a balance of restraint and passion.

Chinese musical culture predates written history, but many principles crystallized during the Han through Tang dynasties. Court and ritual traditions (yayue) codified pitch standards and modal thinking around the pentatonic system (gong–shang–jiao–zhi–yu), with flexible inclusion of changing and auxiliary tones. Literati aesthetics prized the guqin’s introspective solo art, notational treatises, and music as moral cultivation.

From the Tang era onward, robust exchange with Central and West Asia introduced instruments (e.g., pipa ancestors) and dance-music suites. Regional folk idioms flourished, and urban entertainment cultures gave rise to narrative song and quyi. The Ming–Qing periods saw the maturation of opera systems such as Kunqu and later Beijing opera, uniting melodic patterns (qupai), percussion formulas, role types, and stylized vocalism.

In the late 19th–20th centuries, reformers standardized instruments, expanded ranges, and developed the modern Chinese orchestra (silk-and-bamboo families modeled on Western orchestration). Conservatories codified technique, created new solo repertory for instruments such as erhu, pipa, dizi, and guzheng, and adopted cipher (jianpu) and staff notation. Folk research movements collected regional songs, while composers integrated Western forms with Chinese modality and timbre.

Since the late 20th century, Chinese music spans traditional revival, large-scale concert works, and crossovers with pop, rock, film, and electronic music. International virtuosi and ensembles have made the erhu, pipa, guzheng, sheng, and dizi staples on world stages, while new media amplify styles from classical opera to zhongguo feng pop. Despite this breadth, the genre’s identity continues to center on melodic expressivity, heterophony, and distinctive instrumental color.

Start with the pentatonic framework: gong (1), shang (2), jiao (3), zhi (5), yu (6). Introduce changing/auxiliary tones for color (heptatonic variants), but keep modal centricity clear. Favor stepwise motion punctuated by expressive leaps to structurally important tones (gong, zhi).

Write a clear, singable core melody, then design idiomatic ornaments: portamenti, grace notes, mordents, and wide vibrato specific to each instrument (e.g., left-hand bends on guzheng, bow-pressure slides on erhu, roll/tremolo on pipa). Use rhetorical pauses and cadential sighs to articulate phrases.

Employ flexible rhythm: free-tempo preludes (sanban) can lead to metered sections. For metered music, draw on percussion cycles and cues from opera bands or Jiangnan sizhu. Use sectional forms built on qupai (fixed-tune) variation, or compose narrative suites with contrasting tempi and textures.

Combine silk-and-bamboo timbres: erhu or dizi for the melodic line, guzheng/pipa for arpeggiated support and counter-ornamentation, sheng for sustained tone clusters and drones, and a small percussion battery (gongs, cymbals, tanggu) for punctuation. Aim for heterophony—multiple parts elaborating the same melody—rather than chordal harmony.

Treat vertical sonorities as color and resonance, not functional harmony. Use open fifths, parallel fourths/fifths, drones (on gong or zhi), and timbral doubling. Reserve dense textures for climaxes; otherwise, emphasize clarity and space.

Sketch in jianpu (cipher) to keep modal planning transparent, then orchestrate for idiomatic ranges and ornaments. Consider a free-rhythm introduction, a lyrical middle section, and a brilliant fast finale. If fusing with modern production, preserve acoustic timbres, close-mic ornamentation, and room ambience, adding subtle pads or low drones that reinforce modal centers without overpowering the heterophony.