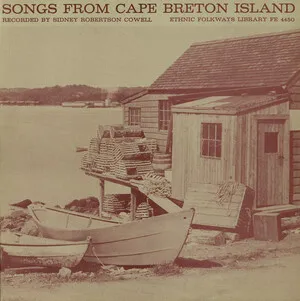

Cape Breton folk music is the traditional music of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada, rooted primarily in Scottish Gaelic fiddle and song traditions that were carried across the Atlantic by Highland immigrants in the late 18th and 19th centuries. It preserves older Scottish dance forms—strathspeys, reels, jigs, and marches—while absorbing influences from Irish, Acadian/French-Canadian, and local Maritime musical practices.

A defining sonic feature is the driving, syncopated piano accompaniment behind the lead fiddle, with muscular bass runs, chordal vamps, and rhythmic lifts designed for step-dancing. Fiddle technique emphasizes strong bowing, the “Scotch snap” in strathspeys, drones and double-stops, and brisk reel tempos tailored to social dances. Alongside instrumental sets, Gaelic song—mouth music (puirt-à-beul), milling songs, and narrative ballads—remains integral, often performed unaccompanied or with sparse backing.

The result is a vibrant, dance-centered tradition that feels both antique and immediate: an Atlantic Canadian expression of Gaelic culture that has become internationally renowned for its energetic fiddle playing, percussive step-dance, and living community of players and dancers.

Highland Clearances and voluntary emigration brought thousands of Scottish Gaels to Cape Breton Island. They carried a robust fiddle and dance repertoire—strathspeys, reels, jigs, marches—and Gaelic song traditions. Relative geographic isolation allowed these forms to persist with fewer stylistic changes than in Scotland, while daily life (milling frolics, house parties, parish events) sustained the music and dance.

Through the 20th century, music circulated via family lineages, house sessions, local dances, and regional radio. Piano accompaniment, now a hallmark of the style, matured into a propulsive, bass-driven idiom tailored for step-dancing and square sets. Fiddlers standardized tune-set structures (e.g., strathspey-to-reel transitions) for dancers, and Gaelic song continued in community and church contexts.

Commercial recordings, festivals, and national broadcasts introduced Cape Breton’s sound across Canada and abroad. Influential fiddlers codified repertoire and style on LPs and tune books, helping define a modern canon. Tours to Scotland and Ireland fostered a notable feedback loop: Cape Breton players influenced Celtic revivals overseas even as they reaffirmed their own Gaelic roots.

Artists such as Natalie MacMaster and Ashley MacIsaac brought the music to global stages, while ensembles blended tradition with contemporary arrangements. The Celtic Colours International Festival became a key showcase and exchange point. Today, music camps, school programs, and intergenerational sessions keep transmission strong, with ongoing repertoire growth and collaborations across the Celtic and folk worlds.