Burushaski folk music is the traditional music of the Burusho (Burushaski-speaking) communities of Hunza, Nagar, and Yasin in the high valleys of Gilgit–Baltistan, northern Pakistan. It is a largely oral, community-based tradition whose songs mark the rhythm of everyday life—weddings, harvests, seasonal migrations, lullabies, heroic ballads, and devotional gatherings.

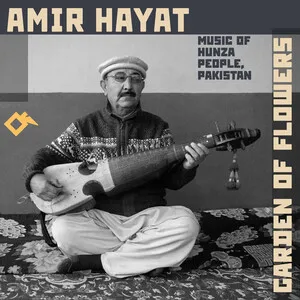

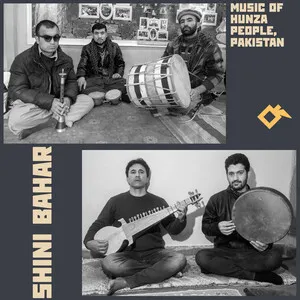

Musically, it favors modal melodies carried by solo voice or small choruses over a sustained drone, supported by earthy percussion and piercing ceremonial winds. Common instruments include the rubab (lute), dhol/daman (double-headed drum), daf (frame drum), surnai (shawm), bamboo flutes (e.g., bansuri), and the jaw harp (chang). Texts are in Burushaski, with poetic images of mountains, rivers, orchards, and kinship ties, and with devotional poetry reflecting the region’s Islamic (predominantly Ismaili) heritage.

Compared with lowland South Asian styles, the sound is lean, open, and heterophonic: multiple voices or instruments ornament the same tune with slight variations. Dances at weddings and festivals often use steady duple or compound-duple rhythms, while narrative and pastoral songs flow with freer, speech-like rhythm.

Burushaski folk music grew from the daily and ceremonial life of mountain communities that farmed terraces, herded in high pastures, and traded across the Karakoram. Long before formal documentation, village bards and family singers maintained repertories of wedding songs, laments, lullabies, and epic tales transmitted orally.

Between the 18th and 19th centuries, small princely courts in Hunza and Nagar patronized musicians for festivals, receptions, and martial displays. Processional bands of dhol (or daman) and surnai provided a sonic emblem for communal rituals, while itinerant rubab players and storytellers circulated songs and styles along trade routes linking South Asia, the Pamirs, and Persianate Central Asia.

In the mid–late 20th century, migration, education, and radio broadened access to neighboring musics. Yet local weddings and seasonal festivities remained the core of transmission. Community recording initiatives and cultural troupes began to document older repertories, while amplified rubab, frame-drum sets, and bamboo flutes entered staged performances.

In the 21st century, cultural centers and regional festivals in Gilgit–Baltistan support teaching, archiving, and performance. Youth ensembles mix traditional instruments with light amplification and modern arrangement, but the heart of the genre still lies in intimate village settings—call-and-response choruses, circular dances, and narrative songs sung in Burushaski that encode memory, place, and identity.