Buganda royal court music is the ceremonial and highly codified musical tradition of the Kingdom of Buganda (central Uganda), historically performed for the Kabaka (king) and the royal court.

It features interlocking xylophone ensembles (amadinda and the larger akadinda), tuned drum orchestras (notably the entenga of 12 pitch-tuned drums and entamiivu court drumming), royal harp (ennanga), lyre (endongo), side-blown flute (endere), and distinctive families of drums used for processions and palace rites (including the celebrated royal drums, Mujaguzo).

The style is marked by dense hocketing textures, cross‑rhythms in cyclic timelines, resultant-melody effects from interlocking parts, and praise poetry for the Kabaka. Performances range from stately, ritual pieces to dance-accompaniment drumming tied to royal dances such as Baakisimba, Nankasa, and Muwogola.

Music in Buganda predates the formal court, with hereditary musician guilds, drum families, and praise-poetry traditions that gradually coalesced around the Kabaka’s palace. By the 18th–19th centuries, these practices were consolidated into court ensembles with defined repertoires, functions, and custodial lineages.

Under Kabakas such as Ssuuna II (r. 1832–1856) and Mutesa I (r. 1856–1884), major court ensembles were formalized. The entenga (a 12‑drum tuned orchestra) and the akadinda/amadinda xylophones achieved high prestige. Instrument tunings were aligned so that harp (ennanga), lyre (endongo), flute (endere), xylophones, and tuned drums could share melodic material, enabling interlocking performance practice and elaborate praise music for royal ceremonies, audiences, and processions.

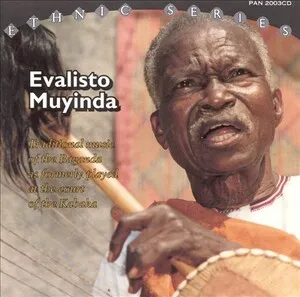

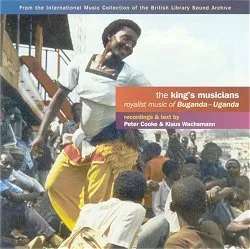

During the colonial period and into the mid‑20th century, court music remained a cultural emblem. Ethnomusicologists and recordists (notably Klaus Wachsmann and later Peter Cooke) documented palace repertoires and techniques, producing influential analyses and landmark recordings that brought Buganda court music to global attention.

In 1966, political upheaval and the abolition of traditional kingdoms disrupted palace institutions. Many royal musicians dispersed, instruments were hidden or lost, and performances shifted to cultural troupes, schools, and community contexts to preserve the repertoire.

With the restoration of cultural kingdoms in the 1990s, royal symbolism and selected court practices re-emerged. Musicians and educators revived and reconstructed entenga and xylophone repertoires, while ensembles associated with universities, cultural troupes, and the Buganda court re‑established performance practice. Today, the music functions as a living heritage: it is performed in palace contexts, at cultural events, and in staged presentations, while continuing to influence Ugandan popular genres and international scholarship on interlocking rhythm and cyclic form.