Brazilian classical music is the art-music tradition of Brazil, spanning from colonial-era Baroque and Classical sacred works to Romantic opera and 20th/21st‑century modernism and post‑modern currents.

It fuses European formal practices (counterpoint, sonata, orchestral writing, liturgical forms) with Brazilian rhythmic and melodic idioms drawn from modinha, lundu, choro, and, later, samba and baião, as well as indigenous and Afro‑Brazilian musical languages. This blend yields a palette of vibrant rhythms, lyrical lines, and bold orchestral colors—epitomized by Heitor Villa‑Lobos’s synthesis of Brazilian folk materials with neo‑Baroque and modernist procedures.

Across its evolution, the genre encompasses sacred and secular music, operas, symphonies, concertos, chamber music, and choral works. Its signature is a flexible rhythmic vitality, strong melodic profile, and timbral imagination that reflect Brazil’s cultural diversity while speaking fluently to international classical forms.

Brazilian classical music emerged in the 18th century within church and courtly spheres, especially in Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro. Composers such as José Joaquim Lobo de Mesquita and André da Silva Gomes wrote masses, motets, and instrumental works in late Baroque and Classical styles, shaped by Portuguese liturgical traditions and local performance practice. Father José Maurício Nunes Garcia (1767–1830) became the leading figure of the turn of the 19th century, creating refined sacred and secular music that bridged Classical elegance and early Romantic expressivity.

In the imperial period, opera and concert life flourished. Antônio Carlos Gomes (1836–1896) achieved international fame with operas like "O Guarani," combining Italianate Romanticism with Brazilian themes. Art song (modinha) and dance (lundu) informed the melodic and rhythmic idiom of concert works, while salons and emerging conservatories professionalized training and performance.

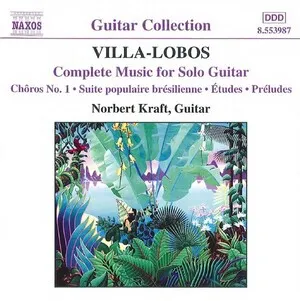

Heitor Villa‑Lobos (1887–1959) defined a modern Brazilian voice by integrating folk and urban genres (choro, modinha) and indigenous/Afro‑Brazilian elements with Bachian counterpoint and modernist harmony. Works like "Bachianas Brasileiras" and "Choros" cycles exemplify this synthesis. Parallel nationalist currents continued with Camargo Guarnieri and Francisco Mignone, who drew on popular rhythms while maintaining rigorous craft.

Post‑WWII composers—Cláudio Santoro, César Guerra‑Peixe, Edino Krieger, Radamés Gnattali—explored serialism, neoclassicism, and crossovers with popular idioms (e.g., choro/samba with orchestral writing). Institutions, orchestras (e.g., OSESP), and festivals expanded the platform for new music and large‑scale works.

From the late 20th century onward, composers such as Almeida Prado and Marlos Nobre advanced post‑tonal, spectral, and coloristic approaches while remaining conversant with Brazilian rhythmic DNA. Today’s landscape is stylistically diverse—spanning historically informed performance of Minas Gerais Baroque to cutting‑edge chamber and orchestral music—yet consistently marked by a lyrical sensibility and rhythmic vitality rooted in Brazil’s cultural mosaic.