Your digging level

Description

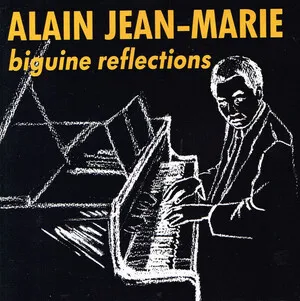

Biguine is a lively Afro-Creole dance music that originated in Martinique and Guadeloupe and later took Paris by storm in the interwar years. Its groove fuses African-derived drumming and stick patterns with European ballroom dances, producing a buoyant, syncopated feel in duple meter.

Traditionally led by clarinet, trombone or trumpet with banjo/guitar, bass, and hand percussion (ti bwa sticks, chacha/maracas, and drums), biguine alternates catchy, ornamented melodies with call-and-response riffs. Harmonically it favors bright, diatonic progressions with dance-friendly phrasing, making it equally at home in street parades, salon dances, and concert settings.

History

Biguine emerged in the 1830s in and around Saint-Pierre, Martinique, where African-descended communities blended local bélé rhythms (drum-and-dance forms accompanied by ti bwa stick patterns) with imported European dances such as the mazurka, polka, and waltz. This creolization produced several variants—from outdoor, processional styles to more refined salon forms—united by a distinctive, syncopated duple-time pulse.

After the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée, many Antillean musicians relocated to Fort-de-France and, crucially, to Paris. In the 1920s and 1930s, biguine became a sensation in Parisian bals nègres and cabarets, amplified by the 1931 Colonial Exposition. Clarinetist-bandleader Alexandre Stellio, along with musicians like Ernest Léardée, codified a modern ensemble sound—clarinet or trombone lead, banjo/guitar, double bass, and hand percussion—captured on 78 rpm records. Interaction with jazz aesthetics (arranging, soloing, and phrasing) gave rise to a “biguine-jazz” approach without losing the core Antillean rhythm.

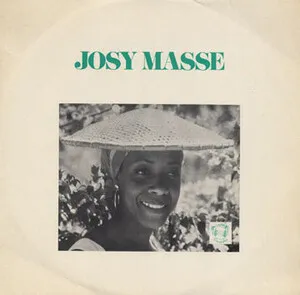

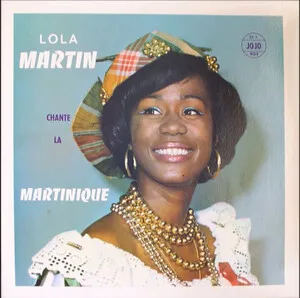

Through the 1940s–1960s, biguine remained central to Martinican and Guadeloupean dance culture. Street-oriented and salon-oriented variants coexisted, while bands integrated elements from related local traditions like gwo ka (Guadeloupean drumming) and continued dialogue with jazz. Artists and orchestras kept the repertory vibrant at dances, carnivals, and on radio.

From the 1970s onward, ensembles such as Malavoi and La Perfecta revived and modernized biguine and sister genres (e.g., Antillean mazurka), often orchestrating strings or brass and incorporating jazz harmony. Although 1980s zouk would become the dominant Antillean pop, it drew on the rhythmic DNA of biguine (alongside bélé, gwo ka, and others). Today, biguine persists as both a heritage dance music and a stylistic resource for Antillean jazz and contemporary Caribbean fusions.