Baisha Xiyue (Baisha “fine music”) is a classical Naxi instrumental ensemble tradition from Baisha Village near Lijiang, Yunnan, China. It is performed by community ensembles and is considered one of the oldest living repertoires of the Naxi people.

The music features a heterophonic texture in which multiple instruments render the same melody with individual ornamentation and subtle rhythmic offsets. It is largely modal and pentatonic, paced at moderate to slow tempi, and articulated with refined, unforced tone production. Typical instruments include dizi and xiao (flutes), sheng (mouth-organ), guan/guanzi (double-reed), bowed huqin family instruments (e.g., erxian), plucked lutes such as pipa and sanxian, and a discreet percussion battery (ban/clappers, muyu/woodblock, small cymbals, and hand drum).

Repertoire is organized around qupai (fixed melodic models/tunes), often traced by oral transmission to a legendary set of “twenty-four pieces,” and elaborated through variation, sectional contrast, and flexible meter. The style blends courtly Han Chinese ritual/literati aesthetics with local Naxi musical sensibilities, producing a contemplative sound suited to ceremonies and community gatherings.

Local tradition associates Baisha Xiyue with the early Ming period, when repertoire linked to Central Plains court and ritual music was introduced to the Naxi chieftaincy in Lijiang. Oral accounts describe a bestowed set of pieces—later remembered as “twenty-four tunes”—that were adapted by Naxi musicians. The resulting ensemble style took root in Baisha, the historical Naxi center north of Lijiang.

Through the 15th–19th centuries, Baisha Xiyue was maintained by village-based amateur associations. Its repertoire, structured around qupai (fixed tunes), was transmitted orally, sometimes aided by gongche solmization, and performed on wind, plucked, and bowed instruments with light percussion. The music’s hallmark is heterophony—simultaneous melodic lines with individual ornamentation—within pentatonic modes and flexible tempo frameworks that accommodate free-meter introductions and more measured sections.

Like many traditional musics, Baisha Xiyue faced interruptions in the mid-20th century, including periods when performance was curtailed. From the late 1970s onward, local elders, culture workers, and researchers led documentation and revival efforts in and around Lijiang. Associations and village ensembles resumed public performances, and the music became recognized as an important element of Naxi cultural heritage.

Today Baisha Xiyue is sustained by community ensembles in Baisha and nearby towns, performed at cultural events, and presented to visitors in educational concerts. Its repertoire and performing practice are safeguarded under China’s intangible cultural heritage framework, with ongoing efforts to train younger inheritors while preserving the style’s understated, ensemble-centered aesthetics.

Use Chinese pentatonic modes (gong, shang, jue, zhi, yu) and avoid strong functional harmony. Cadences typically resolve to the modal center with stepwise approach and ornamental turns rather than dominant–tonic motion.

Base pieces on qupai (fixed tunes). Structure a performance as a suite: begin with a free-meter (sanban) introduction to outline the mode and principal motifs, then proceed to measured sections with gentle rhythmic cycles. Employ variation techniques—ornamentation, octave displacement, and figurations—while keeping the underlying tune recognizable.

Write for a heterophonic texture: multiple instruments carry essentially the same melody, each with individualized ornaments and slight rhythmic asynchrony. Keep dynamics moderate and timbres mellow; the aim is collective blend rather than soloistic projection.

Combine winds (dizi, xiao, sheng, guan/guanzi), plucked lutes (pipa, sanxian), and bowed huqin family instruments (e.g., erxian). Add light percussion (ban/clappers, muyu/woodblock, small cymbals, frame or barrel drum) to articulate entries and cadences rather than drive heavy pulse. Let the flute or guan lead phrases; sheng sustains harmonic fields; plucked and bowed instruments provide rhythmic subtlety and inner motion.

Favor moderate to slow tempi with breathing room between phrases. Use elastic tempo (ritardandi and slight rubato) at ends of lines. Rhythmic cycles can be implied rather than strictly counted; percussion should cue transitions and closures.

Apply traditional ornaments—grace notes, slides, mordents, and gentle vibrato—tailored to each instrument. Prioritize smooth legato lines with clear phrase endings, leaving short silences to shape the contour.

Sketch the core tune in gongche or staff notation, then workshop heterophonic realizations with performers. Encourage elders’ stylistic input, align on cadential cues, and refine balance so the lead voice is audible without overpowering the ensemble.

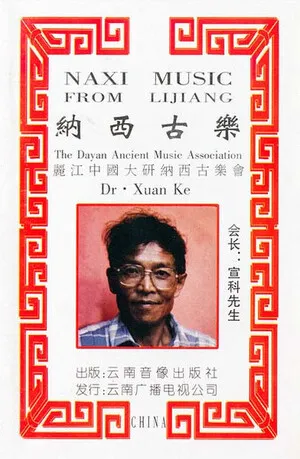

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)

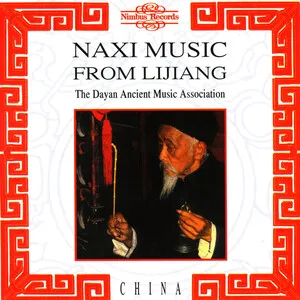

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)