Australian folk music refers to the body of traditional and revivalist songs, tunes, and dance music that took shape in Australia from the early 19th century onward. It blends Anglo‑Celtic ballad and dance traditions brought by convicts, settlers, and gold‑rush migrants with themes, landscapes, and vernacular distinctive to life in the Australian bush.

Its core repertoire includes bush ballads and working songs about shearers, drovers, miners, sailors, swagmen, and outlaws, often sung in a plain, communal style with strong choruses. Typical instruments include fiddle, button accordion, tin whistle, concertina, banjo, guitar, harmonica, lagerphone, bones, and spoons, with rhythms drawn from polkas, waltzes, schottisches, mazurkas, and hornpipes.

Over time, the tradition has interacted with First Nations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) music and storytelling, and it has informed modern singer‑songwriters and folk‑rock acts. The result is a repertoire that is at once local in imagery and language yet recognizably part of the wider British and Irish folk family.

Convicts, sailors, and settlers brought English, Irish, and Scottish ballads, dance tunes, and sea shanties to Australia in the early 19th century. In pastoral stations, shearing sheds, and on the goldfields of the 1850s, these forms morphed into local bush ballads and work songs that documented frontier life. Canonical songs such as The Wild Colonial Boy, Click Go the Shears, and Waltzing Matilda (lyrics collected and adapted by A.B. "Banjo" Paterson in the 1890s) exemplify this period. Tunes were commonly played on fiddle, concertina, and button accordion for bush dances (polkas, waltzes, schottisches), while verses were delivered in a straightforward, communal manner suited to camp and pub singing.

As urbanisation grew, music‑hall and parlour‑song influences entered the repertoire, while rural bush music persisted in regional communities. Bush poetry (Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson) reinforced the narrative, larrikin humour, and working‑class sensibility that would characterise the song tradition.

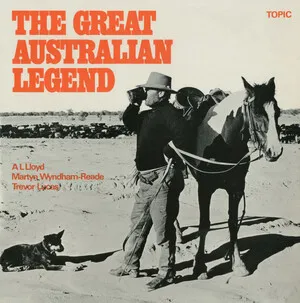

From the 1950s, collectors such as John Meredith and Warren Fahey recorded older singers and shearers, preserving hundreds of songs and tunes. The Bush Music Club (founded 1954 in Sydney) fostered playing, dancing, and publishing. Internationally connected revivalists (including A.L. Lloyd, who had worked in Australia) helped place Australian material within a broader folk context. Bush bands—most prominently The Bushwackers—popularised dance sets and choruses, while contemporary writers like Eric Bogle crafted new, socially aware ballads (e.g., "And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda").

Folk‑rock groups such as Redgum brought protest and storytelling into the pop charts ("I Was Only Nineteen"), and singer‑songwriters and acoustic ensembles continued the narrative tradition. Major festivals—the National Folk Festival (Canberra), Port Fairy Folk Festival (Victoria), and Woodford Folk Festival (Queensland)—became hubs for performance, dance, and tradition‑bearing. Increasingly, collaborations and dialogue with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists highlighted First Nations perspectives and deepened the repertoire’s sense of place, while maintaining continuity with Anglo‑Celtic dance and song forms.

Australian folk is marked by plainspoken storytelling, sing‑along choruses, danceable set tunes, and themes of work, landscape, mateship, and social justice. It remains both a participatory community practice (bush dances, sessions, singarounds) and a professional performance tradition that continues to evolve.